The petition to the City Council was straightforward: Enact a mandatory mask policy to combat the pandemic, or “the disease will come back again and will exact a heavier toll than ever.”

Seven hundred residents, doctors and concerned citizens alike, signed the document. But the council members who heard their pleas wouldn’t have it.

One said masks left the wearer “breathing in the foul air which they exhale.” Another cracked he might be more sympathetic to the issue “if the doctors would come through and agree on some one thing, or if any of them could agree at all.” Still another said he would “not propose to take the advice of a lot of outsiders.”

And so the petition failed — even as five of nine council members who mulled it over either suffered from the virus or had to quarantine because their family members had it.

Huntington Beach, 2020? Try Los Angeles, 1919.

For over a century, historians and health officials have marveled at how Los Angeles weathered the so-called Spanish flu better than most major American cities. Most of the credit goes to City Health Commissioner Dr. Luther Powers, who ordered business and school shutdowns early on to flatten the curve while other metro areas didn’t.

But Powers never implemented a mask ordinance, despite having the power and multiple opportunities to do so.

The non-move might serve as vindication to today’s pandejos and maskholes, who use a lot of the same whines that their counterparts did a century ago. But a look back at the face-off between maskers and anti-maskers during the height of the Spanish flu actually offers a cautionary tale that should haunt us today:

“There are a variety of variables” to explain why Los Angeles suffered less than other towns, said J. Alexander Navarro. He’s a medical historian at the University of Michigan who helps edit the school’s online Influenza Encyclopedia, the nation’s most comprehensive public archive of the 1918 flu. But if Powers had required everyone to wear masks in public, that “would’ve had an impact.”

In 2007, Navarro co-authored a paper in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. that found that cities which instituted multiple “non-pharmaceutical interventions” — quarantines, social distancing, masks and the like — suffered less than those that went with one or none. He compared the strategies to, of all things, slices of Swiss cheese.

“They all have holes,” Navarro said. “Alone, they’re not effective. But if you stack them together, you start to layer up those slices, and one of those holes don’t go the whole way.”

This is how Powers dealt Los Angeles a metaphorical bag of shredded cheddar.

The widespread use of masks in Los Angeles seemed imminent when the Spanish flu slammed California in the fall of 1918. San Francisco issued a citywide order for anyone outside their homes; San Diego required them for anyone serving the public, like restaurant employees or bank tellers.

Gov. William D. Stephens, running for reelection, urged Californians to wear masks, opining that the practice offers “but little discomfort and means a service rendered to our fellow-men and to our country.”

This quick mainstreaming had an immediate impact on the public. The Times reported on Oct. 23 that masks around Los Angeles “were quite common in large offices … where the general public is coming and going all day in numbers.”

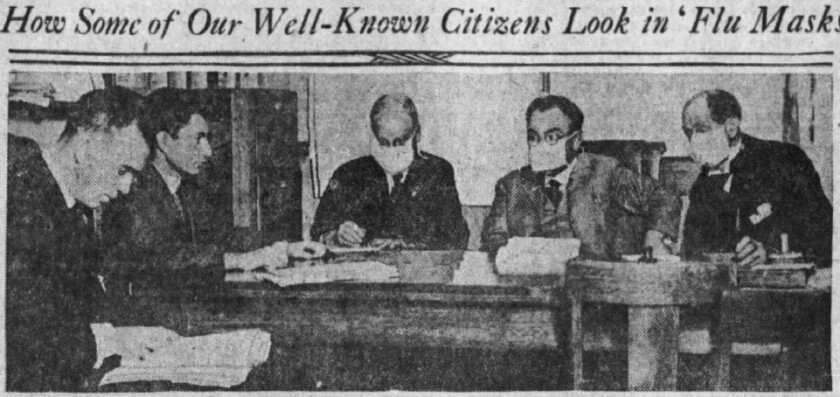

Oct. 24, 1918, photo in Los Angeles Times of the city’s draft board during a desertion hearing. (Los Angeles Times archives)

The following day, L.A. Mayor Frederick Woodman brought a resolution to the City Council to enforce mask wearing, and even donned one in support of the cause.

But the measure went nowhere, mostly because of Powers.

“The impossibility of educating all at once the mass of the people as to how to use the masks properly is obvious,” he told the council. “When care is not exercised, the masks are useless.”

The council went on to pass a resolution that merely advised the public to use masks, instead of making them obligatory.

The matter came back two weeks later and was rejected again. By then, Powers had penned a bulletin published in the city’s dailies that asked Angelenos “respectfully” to wear a mask so everyone could “benefit by willingly entering into this public duty without being forced.”

Nov. 7, 1918, bulletin by Los Angeles City Health Officer published in Los Angeles Times that urged Angelenos to wear masks in public. (Los Angeles Times archives)

This time, the council was now hostile to the idea, with President Bert Farmer stating, “All this talk about making the wearing of masks compulsory sounds to me like bunk.”

Cases and deaths were dropping at the time, so that lulled a public and press once receptive to a mask ordinance to now ignore them altogether, if not outright ridicule their use.

“In going the distance six or seven masks might be encountered,” The Times wrote about the Thanksgiving Eve scene that year in downtown L.A., “while from fifty to seventy-five people without masks were sneezing and coughing as they hurried along, apparently unmindful of other people’s germs and not stingy with their own.”

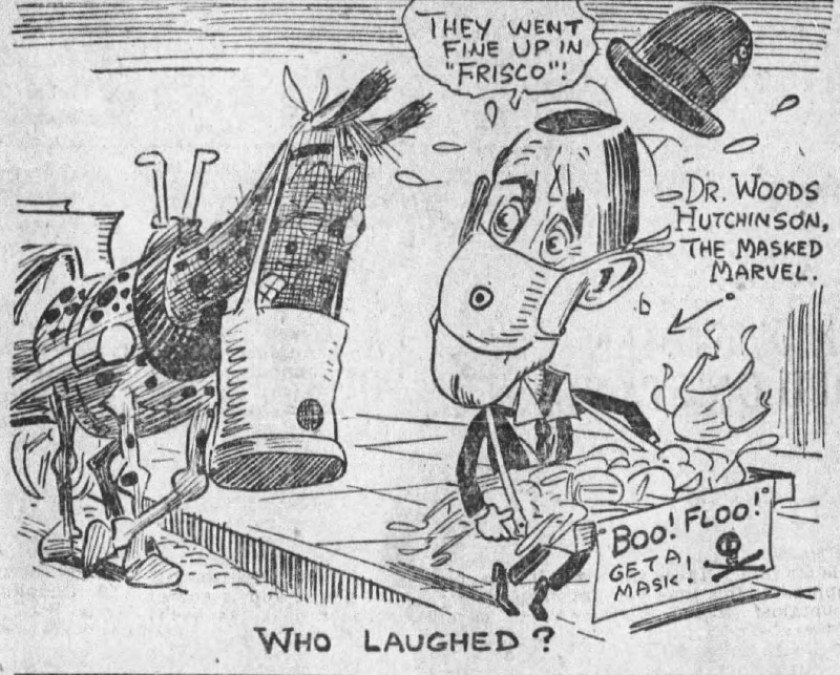

By then, this paper openly referred to masks as “muzzles,” published editorial cartoons mocking their advocates, and opined “it is might hard for a man to look like statesman when he goes forth on the thoroughfares with his mush embedded in a gauze nosebag.”

In a Dec. 1, 1918, editorial titled “Adios ‘Flu’ Scare!” the paper’s editorial board wrote there was no proof that any preventive measure “averted a single case of the disease or saved a single life. The real sufferers are the men and women whose incomes have been stopped, whose businesses have been all but ruined.”

The Times spoke too soon: The city was just about to get walloped by a second wave.

By January, as Los Angeles weathered yet another wave, Powers finally wrote up a mask mandate but decided to hold a public hearing on the matter. That’s when a group calling itself the Citizens League to Aid the Suppression of Influenza presented the petition signed by more than 700.

But just before the meeting, the California State Board of Health issued a memo that said mask policies have “no effect whatever” in stopping the flu yet recommended their use due to the “theoretical possibilities” of preventing the spread.

L.A. Police Chief John Butler said he thought it would be hard to enforce any measure “but asserted that the police department would do the Health Department’s bidding at any and all times.”

At the end, the council — though skeptical — deferred to Powers.

“I shall not recommend the passage of a flu mask ordinance today,” he said.

The myth that masks did nothing to stop the flu burrowed itself into the Angeleno ego. The Times published charts that showed how cities that enacted face-cover policies suffered far worse than L.A. And, in a particularly cruel volley in the eternal rivalry between us and San Francisco, this paper labeled the latter “City of Masks” in a Jan. 21 story boasting that their “flu toll is far above ours.”

Jan. 21, 1919, Los Angeles Times headline. (Los Angeles Times archives)

A week later, The Times’ editorial board pilloried the “many physicians” who had asked for a mask ban, proclaiming that the State Board of Health found “conclusively that the compulsory wearing of masks does not affect the progress of the epidemic.”

“Again the people of Southern California,” this paper concluded, “can give thanks that they live in an exceptionally favored land.”

Powers never fully explained his opposition to mask decrees despite his personal belief that everyone should wear one. But one thing is certain: The debate featured none of the rancor about tyranny and liberties that dominates the conversation right now.

“The big difference, today it’s much more partisan and politicized,” Navarro said. “It might’ve come down to personal ideology [during the Spanish flu], but that didn’t translate into national politics in the way it has today.”

In a Department of Health report to the City Council that addressed the Spanish flu, Powers admitted that his team “was ill prepared to take on any extra work, much less the control of such a severe and rapid epidemic.”

He did not mention the debate over face coverings but did say any spikes happened “to a great extent upon the holidays and increased or diminished by contacts or exposure.”

Now, imagine if he had mandated masks.

(Los Angeles Times).