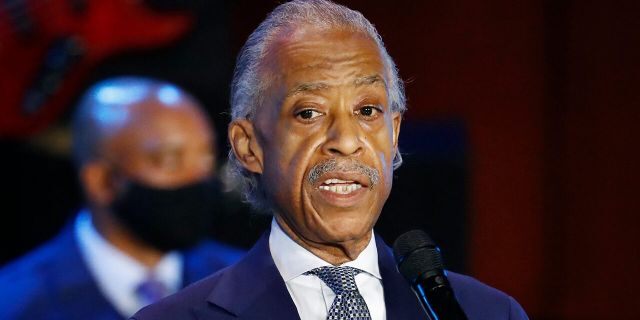

The Rev. Al Sharpton is an apt example of the painful contradictions between fighting racism and fighting anti-Semitism.

Fighting racism doesn’t necessarily mean fighting anti-Semitism. Fighting racism can sometimes involve elements of anti-Semitism. And fighting anti-Semitism can sometimes lead to accusations of racism.

If you study the trajectory of racial politics in America in the last 50 years or so, it’s difficult to avoid those three conclusions, as depressing as they are.

Even so, my purpose in raising them here isn’t to discourage American Jews from participating in the new civil-rights movement that has coalesced in the wake of the sickening police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Nor, with deep regret, am I raising them because I’ve come up with an ingenious proposal to resolve these contradictions once and for all. I am raising them only because we need to be clear-eyed about the challenges that lie ahead.

“Get your knee off our necks,” the Rev. Al Sharpton exclaimed at Floyd’s funeral in Minneapolis on June 4, capturing the anger of black communities across the United States at the seemingly unending cycle of police brutality. It is a call to action that resonates powerfully with many Jews (myself included) on the emotional and moral levels.

Headquarters in 1999. (Robert Swanson via Wikimedia Commons).

The Al Sharpton who sounded this clarion call in the presence of George Floyd’s grieving family is the same Al Sharpton who goaded anti-Semitic rioters in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, N.Y., for three agonizing days during the summer of 1991.

“If the Jews want to get it on, tell them to pin their yarmulkes back and come over to my house,” he declared at a rally in Harlem before delivering a eulogy at the funeral of Gavin Cato—the 7-year-old African-American boy whose tragic death in a car accident sparked the rioting—where he invoked the most chilling anti-Semitic tropes. “All we want to say is what Jesus said: If you offend one of these little ones, you got to pay for it,” Sharpton told the mourners. “No compromise, no meetings, no coffee klatch, no skinnin’ and grinnin’.”

Sharpton has never offered genuine contrition for these grotesque remarks, perhaps because they reflect what he genuinely believes, and certainly because there was never any political cost attached to articulating them, Thirty years later, he’s still around, commanding the attention of a new generation of activists. In the struggle against racism in America, you can rest assured they will be told that Sharpton’s record of anti-Semitism is a subordinate concern—not to say an irritation—and those who raise it must be doing so to discredit the goals of the movement.

Sharpton is an apt example of the painful contradictions between fighting racism and fighting anti-Semitism that I outlined at the beginning. The sectarian politics he represents is the antithesis of that iconic image, much treasured by American Jews, of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marching alongside Dr. Martin Luther King in 1965 in Selma, Ala. But in the present political climate, it is the Sharpton approach to black-Jewish relations that has a much greater chance of prevailing.

So, and this is the question confronting the many Jews dedicated to rooting out the cancer of racism from our police departments and from our public institutions more generally, what are you supposed to think when you encounter anti-Semitism as an element in this very same struggle? And what do you do?

As I confessed earlier, I don’t have clear answers, partly because I think we are still diagnosing the nature of the problem. In the last five years, a campaign waged by anti-Zionist groups has pushed the false narrative that American police officers learned the methods of brutality from Israeli military personnel who tested them first on Palestinians. (The evidence provided is laughably flimsy. One claim I came across—that Minneapolis police were “trained” in crowd control by IDF officers—rested entirely on a link to a news report about a one-day anti-terrorism conference that was hosted by the Israeli Consulate in Chicago, which some Minneapolis officers apparently attended. In 2012.)

Yet this readiness to embrace the demonology of Zionism speaks to a deeper problem. Most of the anti-Semitism encountered in black communities in America doesn’t have anything to do with Israel or Zionism. Instead, it is an Americanized version of the Christian anti-Semitism that was adapted by European nationalists and socialists of various stripes over the last two centuries. Its core message is that capitalist democracy is a system designed by Jews to benefit Jews, who then cry out “anti-Semitism!” to pull the wool over the eyes of the masses. Sharpton’s eulogy to Gavin Cato quoted above reflects the journey of those sentiments across the Atlantic.

In both American and Europe, racism against blacks and other communities of color has invariably been a feature of right-wing politics. Contrastingly, anti-Semitism has been a presence on left and right alike, who share the same prejudices about Jews even if they draw slightly different conclusions from them. Despite the preponderance of Jews on the left, raising anti-Semitism as a specific concern in these milieus has historically been treated with suspicion, as an implicit threat to divide the progressive movement over Jewish tribal complaints. In the context of the civil-rights movement in the United States—a country where the historical role played by anti-Semitism has been negligible when compared with racism—complaints of anti-Semitism are frequently presented as a sinister attempt to legitimize the “white privilege” of the Jewish community with the cloak of discrimination.

We are dealing with an old and stubborn formula here, capable of causing real mischief in situations like the one we face as a society now. American Jews are strong enough in their identities not to cast aside the injustices faced by African-Americans simply because anti-Semitism is a factor in the movement against racism in this country. By the same token, we have little choice in recognizing that anti-Semitism will continue to come at us from all sides—and that we should expect, especially when it comes from the left, to have to deal with it on our own.

(JNS).