How comic books taught American kids about the Holocaust

NEW YORK (JTA) — In 2008, famed comic book artist Neal Adams and Holocaust historian Rafael Medoff teamed up to create a comic about Dina Babbitt, a Czech Jewish artist forced by the infamous Dr. Josef Mengele to paint watercolors of Roma prisoners in Auschwitz. They hoped to bring attention to a little-known figure in the Holocaust.

But their work on the comic, published by Marvel, also led them to ponder a larger issue: the surprising degree to which comic books had addressed the genocide in Europe.

“We were surprised and impressed to discover that a number of mainstream comic books had taken on Holocaust-related themes in their story lines at various points over the years,” Medoff, the founding director of the David Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, told JTA in a phone interview last month.

Medoff and Adams — known for his iconic work on DC Comics’ Batman and Green Arrow — decided to explore how a genre aimed at entertaining youths tackled one of history’s darkest chapters.

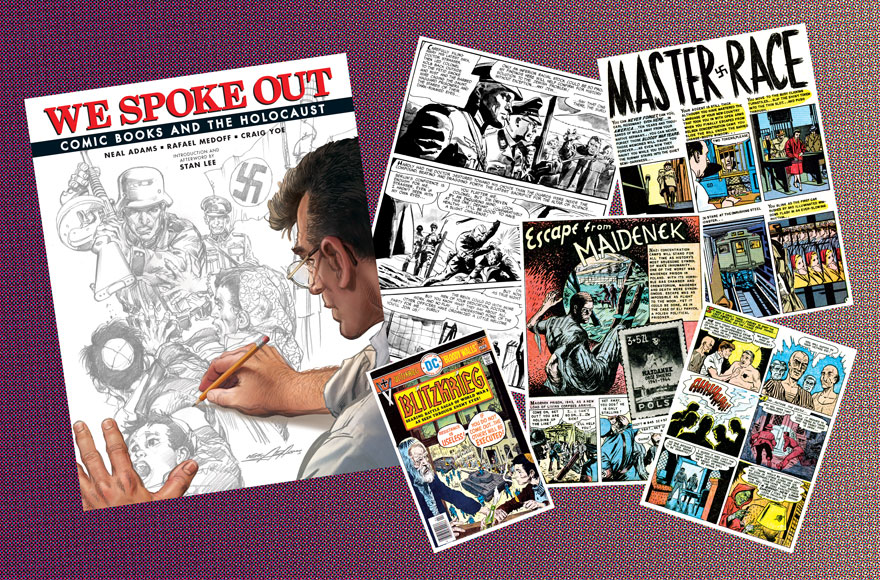

The results of the research is their new book, “We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust,” which was published last month and co-written with author and artist Craig Yoe.

In the decades immediately following World War II, many high school students did not learn about the Holocaust, and TV programs, movies and books only addressed it sporadically, Medoff told JTA.

“It struck us that comic books apparently were one of the ways in which American teenagers were learning about the Holocaust at a time when most of them were not learning about it in school,” he said.

Adams, who designed the book’s cover image, created three of the comics reproduced in full in the book: “Night of the Reaper,” a 1971 comic featuring Batman and Robin and a Holocaust survivor bent on revenge; “Thou Shalt Not Kill!,” a 1972 comic about a golem that kills Nazis in Prague; and “The Last Outrage,” the 2008 comic he created with Medoff about Babbitt’s life.

The book also features three works by the late Jewish comic book icon Joe Kubert, the Polish-born pioneer at DC Comics who founded The Kubert School for budding comics artists.

Captain America, a superhero who fought the Nazis in a comic book series that began in 1940, is featured in a 1979 comic about a Holocaust survivor’s experiences at a fictionalized concentration camp. Notably, it was the first time in the character’s long run that the persecution of the Jews was mentioned.

Many of the 18 comics in the book feature Holocaust survivors seeking vengeance against Nazis, and some present superheroes. Jews wrote about or drew half the comics.

Adams, 76, said comics provide a way to present the horror of the Holocaust in a way that people can “endure it.” As a 10-year-old living in West Germany, where his father was stationed with the U.S. Army, he was shown three hours of footage of concentration camps being liberated. He was so traumatized by what he saw that he did not speak for a week afterward.

‘You’re just seeing it over and over again, the devastation, people living in their own filth, and after a while you just can’t,” he said of the experience. “The idea of this [book] was to take this down to smaller chunks so that people could endure it.”

Yoe said comics also allow readers to take time to think about what they are learning.

“One of the advantages to comics over movies and TV is that you can read at your own pace, especially important stories like these,” he said. “You can stop and ponder a particular panel, or go back and look at the other thing.”

Comics have taken on other weighty issues, including racism, drug abuse and the environment, but such story lines are the exception.

“Most comic book stories of course are just about superheroes chasing supervillains, but there have been many important exceptions to that,” Medoff said.

The authors note several distinct ways the Holocaust was depicted at various times. In the 1950s and early ’60s, comics tended to portray the Holocaust in general terms, without references to Jews as the victims.

“It seemed to me as a historian that this reflected the general mindset in American society at that time, in the ’50s and early ’60s, which was to play down ethnic differences and to universalize the Holocaust as if it was something that kind of happened to everybody,” Medoff said.

In the following decades, he said, writers were more likely to explicitly identify Holocaust victims as Jewish.

Medoff believes the book can be a useful teaching aid in educating about the Holocaust.

“Unfortunately, classroom Holocaust education has not been as effective as we hoped it would be,” he said, citing a recent survey that found that many U.S. millennials lacked basic knowledge about the Holocaust. “[C]omic book stories offer a way to communicate these history lessons to students that might be more effective than some of the ways that have been used until now.”

Adams said that need is especially urgent today.

“Anyone who’s even paying attention to modern politics ought to be warned that if you do not study history, you’re doomed to repeat it,” he said. “We’re on the crux of some very difficult times, and a book like this is a good reminder.”