It can be difficult now to remember what the U.S. economy looked like a year ago. The unemployment rate was 6.7%, with 10 million fewer people employed than before the pandemic. Expectations were that it could take years for the labor market to heal.

Then, the economy experienced two historic surprises. First, demand for workers came soaring back at a velocity almost never before seen. And second, despite companies going all out to hire, millions of workers either retired early or stayed on the sidelines.

These two forces collided to create the most unusual job market in living memory – and an economy afflicted not by too few jobs, but too few workers.

For those looking for employment or to change jobs, the 2021 economy has been a blessing, as companies hike wages and many workers feel empowered to quit because they can swiftly find new opportunities. But the resulting labor shortages are causing profound problems across a range of industries – from restaurants that can’t find servers to factories that can’t find people for the assembly line to hospitals that can’t find nurses.

The shortages are beginning to raise difficult questions about how much some of America’s most vital sectors can continue to rely on a relatively low-paid workforce.

In 2022, something’s got to give. Otherwise, worker shortages could become an enduring feature – or defect – of the U.S. economy.

– – –

How did the labor market get here?

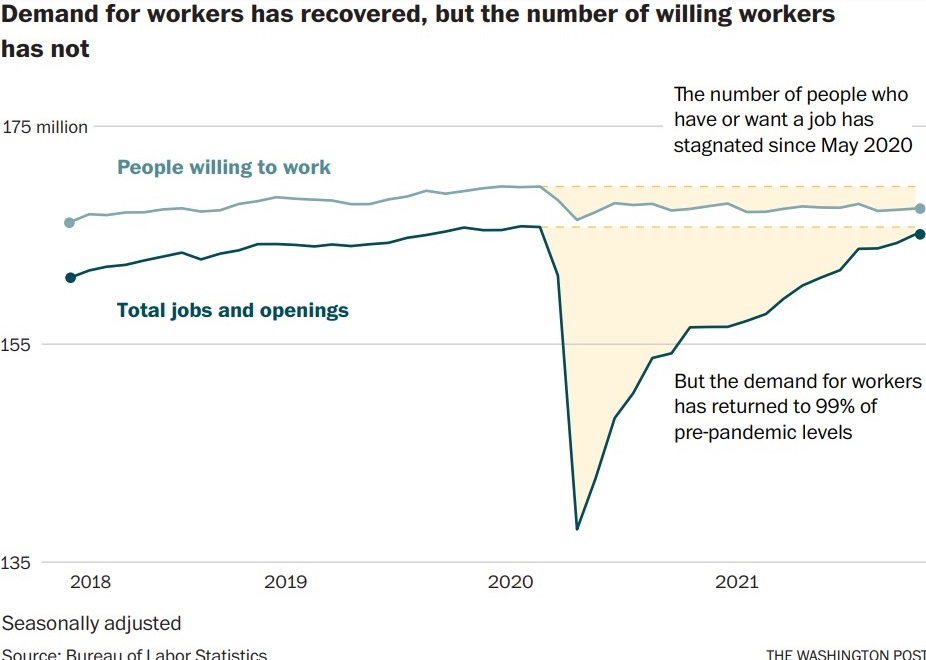

The economy has seldom seen such a mismatch between so much demand for workers and so few people willing to work.

The immediate economic hit from the coronavirus pandemic was unfathomable. In April 2020 alone, nearly 21 million jobs were lost. Despite improvements throughout last year, most economists thought that progress would come slowly in 2021, as anxious, badly burned businesses reluctantly hired.

Instead, it has been a nearly unprecedented recovery.

The unemployment rate, which stood at 4.2% in November, has recovered more rapidly than at all but one point since World War II, the relatively mild recession of 1960.

“2021 was a surprise, I think, to all economists,” said Daniel Zhao, a senior economist at the employment website Glassdoor. “At the beginning of the year, we were concerned about whether we would get a strong enough recovery to get anywhere close to the labor market before the pandemic. And in some ways, we’ve passed that.”

But the desire to hire is only half the story. The problem has been on the other side of the ledger – the number of Americans who are working or looking for work, also known as the labor force.

During the heavy layoffs of 2020, vast numbers of Americans left the labor force, a common pattern during an economic downturn. But usually, as the economy bounces back, people start looking for jobs again.

This time, it hasn’t really happened. Since summer 2020, the labor force participation rate – the share of the population looking for jobs or employed – has hardly budged.

In total, there are still about 3.5 million fewer people employed than there were two years ago. But government statistics show that just over half that number of people – 1.8 million – have joined the ranks of Americans seeking a job.

– – –

Why was there such a strong recovery?

The U.S. economic recovery from the covid pandemic was the strongest of any of the big Western economies. That is in large part thanks to the multiple rounds of government stimulus that totaled at least $5.2 trillion.

Many of these measures poured money directly into Americans’ bank accounts.

Now largely forgotten $600 stimulus checks hit bank accounts as Americans welcomed the new year. And just as that boost began to run out, the $1,400 checks from President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan began to arrive, according to data from the JPMorgan Chase Institute. That was on top of a variety of other stimulus measures, including an expanded child tax credit for families and the extension of enhanced unemployment benefits.

The Biden stimulus pushed the bank accounts of even the lowest-income Americans to unexpected heights. On average, they had more than twice as much in their savings accounts as they did when the pandemic began.

The Federal Reserve, the U.S. central bank that controls interest rates, helped, too. It held rates near zero and pumped hundreds of billions of dollars into the economy.

The twin fire hoses of cash – one from Congress, one from the Fed – sent Americans’ spending roaring back.

The vast majority of that spending went to purchasing goods, from cleaning supplies and home appliances to hamburgers and milk. The service industry, such as hotels and restaurants, saw only a modest boost in spending.

But the spending surge put pressure on the entire labor market. Manufacturers, food processors and all the infrastructure that is involved in delivering goods to stores and people’s homes, such as warehouses and truckers, suddenly had huge demand for workers. Service-sector companies, meanwhile, saw fierce new competition for labor.

– – –

Why didn’t more people want jobs?

Each month since May 2020, a special survey created by the Census Bureau, the Household Pulse Survey, has asked why people aren’t looking for work.

Initially, the answer wasn’t surprising. A large plurality of people cited layoffs and furloughs due to the pandemic. But as hiring recovered, other powerful forces emerged.

An unexpected surge in retirements, along with the continued threat of the coronavirus – which killed more Americans in 2021 than it did in 2020 – kept people from working.

“I think many economists and forecasters in 2021 continually predicted that, this month, people would suddenly explode back into the labor force, whether it’s because of vaccines, or the summer, or schools reopening,” Glassdoor’s Zhao said. “That just fundamentally has not happened.”

Retirements explain a large chunk of the missing workers. For some, soaring retirement accounts and home values, combined with the lower expenses of a simplified work-from-home lifestyle, made it financially feasible to retire early. Others retired solely on Social Security, without retirement accounts to ease the way.

A Washington Post analysis found that over 1.5 million more people were retired in November 2021 than would have been expected based on pre-pandemic trends. Employment has actually declined in the last year among workers who were 55 or older at the start of the pandemic.

Younger workers – those ages 16 to 24 at the start of the pandemic – have bolstered the ranks of willing workers. But that still isn’t enough to balance out the number of older workers who have left.

Retirement isn’t the only force in the worker shortage. The Pulse survey points to other reasons – child care, a simple desire not to work – but the most powerful after retirement is also the most mysterious: “other.”

Nobody knows what “other” refers to, or how long it might endure. Some economists argue that the government benefits that helped fuel consumer spending also enabled more Americans to be pickier about when to return to work. Now that those benefits have ended, more Americans may seek out work.

But it will be hard to catch up. The pool of potential workers has shrunk so much that getting back to the number of people employed before the pandemic would require unprecedented success in connecting job seekers and employers.

Assuming more people don’t start looking for work, it would require an unemployment rate of 2%, lower than at any point since measurement began in 1948.

– – –

What has been the impact on workers?

The exodus of older workers, combined with the spiking demand for labor, has created a superlative market for job seekers. Those who do want to work have almost unprecedented opportunity, particularly in service industries that lost huge numbers of jobs at the start of the pandemic and are still trying to rebuild their workforce.

Workers are quitting their jobs at historically high rates in a phenomenon known as the Great Resignation – higher than any seen since December 2000, when the federal government began tracking quits. But most of those who quit already appear to have another job lined up.

This worker power has translated into the highest wage gains workers in nonmanagement positions have seen in almost four decades.

While many companies are passing those gains on to consumers in the form of higher prices, earnings growth for most workers has outpaced inflation over the past two years, according to a recent analysis by University of Massachusetts at Amherst economist Arindrajit Dube.

Across the economy, lower pay has tended to mean higher wage growth. Nonmanagerial workers in gas stations, the lowest-paid subsector, saw earnings rise 15.9% (to $14.58) since the pandemic began. That’s far above the 10.2% increase seen by the average nonmanagerial worker over that time.

“The whole pandemic has really affected – especially – employees that were stuck in low-wage sectors: restaurants, the hospitality industry,” said Bernard Baumohl, chief global economist at the Economic Outlook Group. “This group is no longer willing to tolerate those kinds of wages and those conditions that they experienced prior to the pandemic and during the pandemic, and they also realize they have a lot more leverage now and are moving out of those low-paying jobs with long hours.”

The long-term effects of this upheaval on the workforce are yet to be seen.

Despite their newfound power in the job market, most workers who left low-paying jobs in restaurants and hotels ended up back in the same industry, according to a recent report from the California Policy Lab. Many of those who didn’t ended up in other low-paying industries, such as retail.

“The fact that workers from the hardest hit sectors in the pandemic typically find jobs in those same sectors may be hindering the path to recovery, especially for low-wage workers,” the report’s authors write.

– – –

What has been the impact on the economy?

What has been a boon for workers has become a crisis for a growing number of industries that are facing severe shortages.

Job openings in industries such as restaurants, hotels and retail are at or near record highs. And some sectors, particularly retail and health care, have barely been able to hire enough people to balance out the number of workers leaving their jobs.

The struggle to hire and retain workers in the food and hospitality sector has dominated headlines since the summer. But in the background, a quieter struggle to staff nursing homes, day cares, schools and other industries has worn away at the foundations of America’s social infrastructure.

The worker shortage is starkest in nursing homes and residential-care facilities, the only industry where employment has declined significantly since May 2020. Lower staffing can mean less attention given to residents and fewer open beds, leaving some patients to languish in hospitals that are already squeezed for space during the pandemic.

Similar challenges have afflicted child-care centers, which have hemorrhaged workers and often can’t afford to increase wages as much as competing employers. Short-staffing in these centers and in public schools has the potential to ripple out through the economy as disruptions to child care cause parents to miss work or drop out of the labor force.

It’s not clear who will fill these workforce holes. The pandemic exacerbated a demographic crunch long in the making. The population is growing more slowly than the economy, and productivity – how much workers can accomplish in any given time period, thanks to technology – isn’t increasing fast enough to make up the difference.

Earlier this month, the Census Bureau estimated 0.1% population growth in the United States in 2021, the slowest rate on record. Other recently released census data indicated that immigration, long a top source of new workers, plunged to its lowest level in at least a decade in 2021.

“If the labor force participation rate doesn’t move and immigration doesn’t recover, then we can’t continue to grow at the pace we otherwise would,” said Marianne Wanamaker, an economics professor at the University of Tennessee and a top economist in the White House during the Trump administration. “We can’t automate fast enough to keep us on track.”

For now, Americans will have to learn to live with too few workers in key aspects of their lives.

If 2021 was a stark reminder of how much the economy depends on low-wage labor, 2022 will be a test of how – and whether – employers and workers can find a new and better balance.

(c) 2021, The Washington Post · Alyssa Fowers, Andrew Van Dam

{Matzav.com}