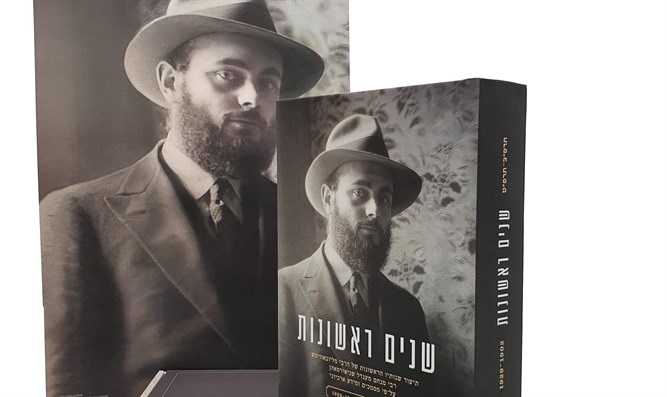

A new book in Hebrew tells the story of the early life of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn.

For fifteen years, documents, letters, and personal diaries were painstakingly collected, telling the story of the early life of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn, known as “the Rebbe.” Now, the book is available in Hebrew.

A new book of over 600 pages in Hebrew tells the story of the early life of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn (an English version was released several years ago).

We spoke to Rabbi Baruch Oberlander, the leading Chabad rabbi in Hungary, about his involvement in the publication of the book.

Rabbi Oberlander says that his work of researching the Rebbe’s early life began through study of the Rebbe’s Torah talks and letters. He would make note of dates and places that appeared in the Rebbe’s Torah writings, and over time he had gathered a large collection of information and documents.

“I began to notice various details that you don’t realize without organized information,” he says.

His partners in the publication began researching the Rebbe’s life by searching through archives in Ukraine and other countries. Rabbi Oberlander’s task remained in the scholarly fields, due to his obligations to the Rabbinate in Hungary.

“We made sure to find the original copy of every document and item, to get good photographs of them,” says Rabbi Oberlander, and the result is the book’s impressive collection of high quality pictures of certificates, letters, photographs, and more.

Does this book have revelations for those who live within the Chabad community, or only for outsiders?

Rabbi Oberlander asserts: “There are many brand new revelations here, even for someone who is well versed in the story of the Rebbe’s life. It is interesting to note that he never studied in a yeshiva. He was taught by private tutors, including his own father, and during his teenage years he studied on his own.”

“A very prominent Yeshiva had opened at the Chabad headquarters in the town of Lubavitch during those years, but the Rebbe nonetheless remained at home.”

According to Rabbi Oberlander, the reason for his study at home was never uncovered. “According to some accounts he wanted to travel to Lubavitch, but that never materialized. We don’t know why.”

“One interesting discovery was the identity of one of his teachers. The Rebbe would tell over the story of how he caught his teacher — a great Torah scholar — studying Torah on Tisha B’Av, when Torah study is prohibited. In his defense, his teacher said: ‘At least I’ll be punished for studying Torah, of all things.'”

“For many decades, we did not know the identity of that teacher. We only knew that he was a Lithuanian, non Chassidic rabbi, who taught the Rebbe until he felt that he had nothing more to offer him. Then, we discovered an article where someone mentioned the teacher with a new, unknown name. We made some investigations, and discovered his identity.”

Rabbi Oberlander told us that they collected a massive treasure-trove of minute details, which covers exact dates and places called from letters, diaries, and original documentation.

“We knew so little about those years that every detail caught my attention. Whenever a person becomes a Rebbe or Rosh Yeshiva, we tend to know everything about the individual from that moment and on, but not from beforehand,” he says.

“There was an interesting friendship between the Rebbe and Rabbi Landau, the chief Rabbi of Bnei Brak,” says Rabbi Oberlander.

“This friendship began when they lived together in Leningrad, and continued for many years. There is an interesting letter in 1948 where the Rebbe tells Rabbi Landau that he doesn’t have Rabbi Landau’s enthusiasm for communal activism. It’s an interesting point, because Rabbi Landau indeed became a city rabbi, but the Rebbe, who described himself as an introvert who did not enjoy crowds and community activity, became phenomenally involved in communal work for the rest of his life.”

Rabbi Oberlander says that they collected enough information for two more volumes: one volume about the Rebbe’s life from his marriage until his move to the United States, and a third volume about his activities in the US until he became the Rebbe.

We asked Rabbi Oberlander if his search uncovered documents or letters that the Rebbe himself would not have wanted publicized. “If there was anything of that sort, it would be only out of humility. We didn’t find anything that wasn’t worthy of publication.”

“When reading through the information we collected, you see that the Rebbe was fully occupied with Torah study and helping his father in his rabbinic duties. He once noted that as a young man he was put through such difficult interrogations as this oldest son of the chief rabbi, that nothing frightens him anymore.”

(Arutz 7).