Jewish community is long gone, but some citizens hope rapprochement will be sealed with approval of transitional legislature so they can get back in touch with their Jewish roots.

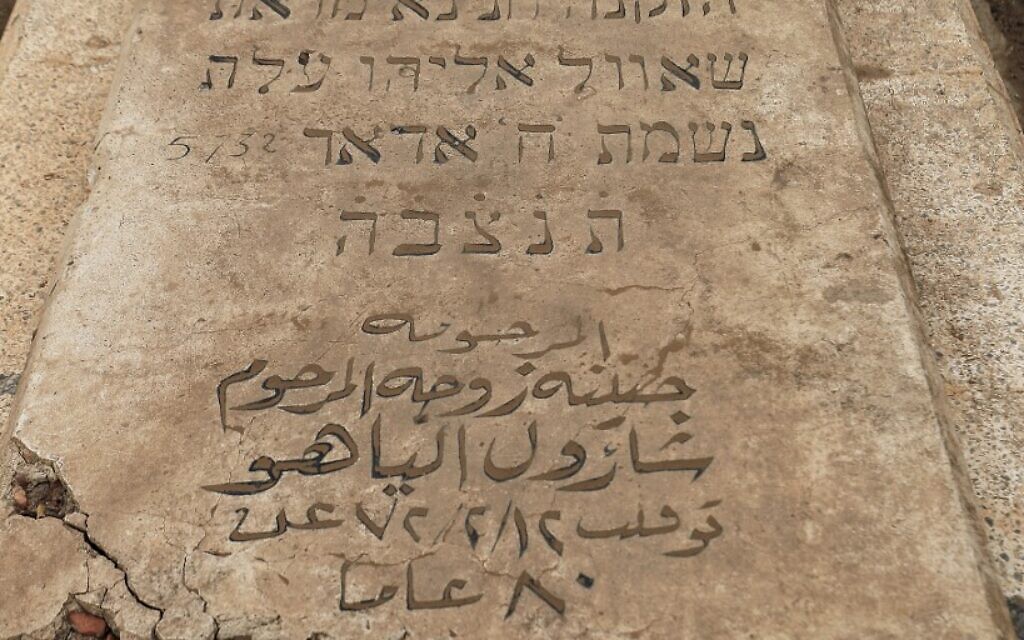

KHARTOUM, Sudan (AFP) — In a corner of a shabby central Khartoum neighborhood, Hebrew-lettered gravestones jut up from a rubble-strewn plot, remnants of the small but vibrant Jewish community that once lived in Sudan.

The cemetery stood for years as a reminder of an oft-overlooked chapter in Sudan’s history, but for decades it has been neglected, abandoned among cracked streets littered with trash and lined by tire shops.

“All we have from Sudan’s Jewish community is this rundown cemetery, some old photos and memories,” pharmacist Mansour Israil told AFP.

The grandson of an Iraqi Jew who settled in Sudan, Israil, whose family later converted to Islam, still lives in a neighborhood once known as “the Jewish quarter” in Omdurman, the capital’s twin city across the Nile river.

The Jewish community in Sudan was already one of the smallest in the Middle East, and it dwindled in the latter half of the 20th century, as tensions surrounding the 1948 creation of Israel permeated the region.

In Sudan, like elsewhere in the Arab world, local Jews bore the brunt of growing anti-Israel sentiment.

“The hearts of many in Sudan changed,” said 75-year-old Israil, who watched his lively, diverse neighborhood transform, and his Jewish friends leave Sudan.

Now, decades later, Israil and other descendants of Sudanese Jews see a recent rapprochement between their country and Israel as an opportunity to connect with their origins.

Last year, Sudan, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Morocco agreed to normalize ties with the Jewish state under the US-brokered Abraham Accords.

It was a U-turn on longstanding policy after the 1967 Six Day War between Arab countries and Israel that saw the Jewish state take control of swaths of territory.

Arab leaders gathered in Khartoum after the defeat, announcing a resolution that became known as the “three nos”: no peace, no recognition and no negotiations with Israel.

At the time, Israil said, he got “threatening phone calls because of my family name.”

“Imagine how it was for the Jews.”

Descendants’ hopes

Pressure on the community had already mounted since the 1956 Suez crisis, when Britain, France and Israel invaded Egypt to regain control over the strategic canal, said Daisy Abboudi, a British historian and descendant of a Jewish Sudanese family.

While Sudan had by then gained independence from Anglo-Egyptian rule, its politics remained closely tied to its northern neighbor.

Sudan’s Jewish community, made up of no more than 250 families at its zenith in the 1940s and 50s, had virtually disappeared by the late 1970s, according to Abboudi, who is also deputy director of UK-based Jewish oral history project Sephardi Voices.

Jewish communities in other Arab states, including Egypt, Morocco and Iraq, had suffered similar fates from the late 1940s.

“It was much more subtle in Sudan compared to anywhere else in the Middle East… but community members started to feel very uncomfortable and realized maybe there is no future” in the country, Abboudi told AFP.

Some of Sudan’s Jewish families resettled in Israel, as were some of the remains from Khartoum’s Jewish cemetery, which were airlifted to Jerusalem and reburied in the 1970s, she said.

Sudan maintained a rigid anti-Israel stance during the three-decade Islamist rule of former president Omar al-Bashir, who was ousted amid mass protests in April 2019.

But six months after the Sudan-Israel deal was announced, the cabinet in Khartoum on Tuesday approved a bill abolishing a 1958 boycott of the Jewish state.

A post-Bashir transitional government has been pushing for re-integration with the international community and to rebuild the country’s economy after decades of US sanctions and internal conflict.

Sudan agreed to normalize ties with Israel in October in a quid pro quo for Washington removing the country from its “state sponsors of terrorism” blacklist months later.

For Salma, Israil’s niece who lives in Wad Madani, south of Khartoum, the move was “long overdue.”

“Normalization will make it easier to reconnect with my origins,” said the 35-year-old, who has sought to learn more about her Jewish roots and the bygone community.

‘Why not Sudan?’

But many other Sudanese are not in favor of the normalization deal.

“There are still obstacles and the government seems a bit hesitant about this move,” Salma said. “Many in Sudan are still resistant.”

While Sudan’s transitional authorities signed the Abraham Accords in January, they maintain the deal will only take effect after a yet-to-be-formed transitional legislature has been approved.

After the signing, dozens of protesters rallied and burned the Israeli flag outside the cabinet offices in Khartoum.

The next month, when a prominent businessman hosted an event promoting religious tolerance that included a speech by a rabbi via videoconference, critics argued it would heighten tensions.

But like Salma, Yosar Basha, also Sudanese of Jewish origins, is “looking forward to when normalization takes effect.”

“I am almost sure we have extended family living in Tel Aviv or elsewhere in Israel that we lost touch with over the years,” Basha said. “Normalization will help us reconnect with our origins.”

And, she added, if other Arab countries “have either normalized or are moving toward normalization” with Israel, “why not Sudan?”