As another unpredictable election plays out, author A.J. Baime tells how support for the Jewish state and civil rights were both central to an underdog incumbent’s campaign.

This year’s American presidential election may contain plenty of twists and turns, but it’s still hard to top the campaign of 1948.

That year, the Democratic incumbent, president Harry S. Truman, faced three rivals — none more formidable than the Republican candidate, Gov. Thomas Dewey of New York. It took place at a time of momentous developments in United States and world history, from the Cold War to the civil rights movement to the creation of a Jewish homeland in the Middle East.

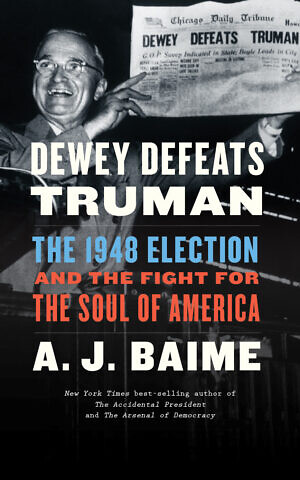

Believing Dewey better equipped for the times, the pollsters and media overwhelmingly predicted his victory. A Chicago newspaper ran “Dewey Defeats Truman” as its front-page headline the day after election day. Yet virtually all got it wrong: Truman won in an upset.

In America’s first presidential election after World War II, Truman won the presidency in his own right after assuming the office after the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The campaign is chronicled in a new book by Jewish-American author A.J. Baime, “Dewey Defeats Truman: The 1948 Election and the Battle for America’s Soul.”

When not writing a column about cars for The Wall Street Journal, Baime pens historical nonfiction books with subjects including the auto industry during WWII and the Ford-Ferrari racetrack rivalry in the 1960s. His new book is his second in a row about Truman. Its title mirrors the fateful newspaper headline, and its cover shows a photo of Truman brandishing a copy.

“In my two books on Truman I wanted to focus on very specific narratives with a beginning, middle, and a climactic end,” Baime told The Times of Israel.

The hot-button issue of Israel threads through the book, including a dramatic moment when the new nation, fighting a war for independence, became an “October Surprise” in the campaign.

Seventy-two years ago on October 28, 1948, Truman learned that without his approval, Secretary of State George Marshall was about to publicly support a UN peace plan named after its mediator, Count Folke Bernadotte. The plan would recognize both Arab and Jewish statehoods in the former British Mandate of Palestine, but it lacked the support of Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s administration.

“The humiliation for the president would be extreme, and it would surely cost him the Jewish vote on November 2,” Baime writes, referring to Election Day that year.

Truman solved the problem by sending Marshall two separate, encrypted cables. One ordered him to make no further comment before consulting with the president. The other requested him to make every effort “to avoid taking position on Palestine” before the day after Election Day, and that if a UN vote preceded that date, the US should abstain.

That evening, at a Madison Square Garden rally, Truman “brought up the main subject of the night: Israel,” Baime writes. “Here in New York — where there were probably more Jews than there were in the Holy Land — he reiterated his support for the Democratic platform. Without committing to de jure recognition of the new Israeli government, Truman pledged his support for the success of this new nation.”

In a phone interview with The Times of Israel earlier this year, Baime called Truman “the first major world leader to support Israel.” Yet, Baime said, “Of all the insurmountable challenges, none were so complex as the issue of the Jewish people, the issue of the Jewish homeland.”

The issue was addressed not only by Truman, but also by some of his campaign rivals — notably Dewey and the Progressive Party candidate, Henry Wallace, who had preceded Truman as the first vice president under FDR. The fourth candidate, South Carolina Gov. Strom Thurmond, focused on defending segregationist policies in the American South as a member of the Dixiecrats, a breakaway party from the Democrats.

By the late 1940s, both Jews and Arabs claimed historic ties to the former British mandate. The Zionist movement sought to create a Jewish homeland whose inhabitants would include survivors of the Holocaust. However, the land was already home to a Palestinian population, and neighboring Arab states opposed the Zionist proposal. The UN pondered how to address the issue. So did Truman.

“Truman really wanted to support the creation of a Jewish homeland,” Baime said. “He was also concerned politically. A lot of powerful donors to the Democratic Party would not donate to the campaign at all unless it supported the nation of Israel.”

One pro-Israel voice in the president’s circle was Eddie Jacobson, an American Jew who served with Truman during World War I. After the war, they partnered in a men’s clothing store in Kansas City. The business went under, but not their friendship. After Truman became president, Jacobson wrote to his friend in support of a Jewish homeland.

Jacobson’s documents and letters were “very moving,” Baime said, describing their message to the president as: “The Jewish people need your help. I want you to give it to them.”

The book shows that Truman sometimes felt frustrated by the Zionists. Meanwhile, the departments of State and Defense opposed a Jewish homeland in the Middle East. At the time, the US imported more oil than it created at home, and they felt that if a new world war erupted with the Soviets, the US would need Middle Eastern oil or face quick defeat, Baime said.

The Arab-Israeli conflict worsened. On September 17, 1948, UN mediator Bernadotte was assassinated by the Stern Gang. A month later, State Department official James Grover McDonald voiced concerns about the fate of 400,000 Palestinian refugees and estimated a death toll of over 100,000 old men, women and children due to conditions of weather and destitution.

Truman’s position on Israel ended up being more measured than what was called for by some Zionists

Truman’s position on Israel ended up being more measured than what was called for by some Zionists and campaign rivals.

Baime noted that the president offered “de facto support,” which was given at the moment of Israeli independence. It was “provisional until the State of Israel would hold a democratic election,” he said.

According to the book, not only did rivals Dewey and Wallace support the Jewish state, they promised more than what Truman was offering.

“It’s important to remember that Tom Dewey was heavily favored to win,” Baime said. “He was a very popular governor of the state of New York, which had the largest population of Jews in America. He was making promises and not beholden to the US State Department or Defense Department. He could more easily promise than Truman could.”

That included a moment on October 22 in which the governor “was tacitly promising that he would grant immediate de jure recognition, or so it seemed,” Baime writes in the book.

Pressed by Dewey’s actions on one end and by Secretary Marshall’s on the other, Truman found a way to reach a conclusion on a complex issue. He faced many such issues, and multiple such tests. In addition to Israeli independence, that year witnessed the integration of the US armed forces, the Marshall Plan (named after the secretary of state), the atomic bomb tests, the Berlin Airlift and the Red Scare.

Of all these issues, Baime said that the president had a particular sensitivity to two: Israel and civil rights.

“A lot of people accused him” of supporting Israel “just so he would secure the Jewish vote,” Baime said. “It offended him. It was not a political move but a moral obligation.”

And, Baime said, “Truman was the first president to go after the African-American vote.” The author noted that Blacks had been denied the vote in many Southern states for generations, and said, “Just like [Truman’s] support for Israel, [civil rights] was a political and moral issue.”

Support for Israel was not a political move but a moral obligation

The issues dovetailed in the closing days of the campaign. After Truman gave his speech on Israel at Madison Square Garden, the next day he visited the Black neighborhood of Harlem for a historic address on civil rights. Between the speeches, Zionists held an all-night vigil at the Biltmore Hotel, which housed the president during his time in New York, and his old friend Jacobson was there for a morning planning session on the 29th.

In the end, there was one more drama: Election Day.

“For many generations after WWI, there were only two events when everybody in America could remember where they were and what they were doing,” Baime said. “Pearl Harbor Day and when they found out Truman was elected.”

Of the latter event, he said, “I knew a way to tell the story in a way that would grab readers. It was not just ‘Truman wins, Dewey loses.’ They would feel the shock of their lives in the climax.”

Overall, the campaign has parallels with today.

“The rise of white nationalism, violence against African-Americans,” Baime said. “The degree to which fear and anxiety gripped the populace. How the candidates were going to address the fear of war with the Soviets, the atomic bomb tests, the Berlin airlift … the Red Scare.”

“People in Washington were all getting nervous about these stories,” Baime said. “Were they facts or conspiracy theories? It’s very relevant today moving into an election. Even around the pandemic, there is so much fear and anxiety today.”

The era’s experts confidently forecast Dewey to win

What made the election so memorable was that the era’s experts confidently forecast Dewey to win. In 2016, the polls similarly predicted victory for Democrat Hillary Clinton over first-time Republican candidate Donald Trump.

“I wonder how many people kick themselves,” Baime reflected. “A lot of Republicans did not come out to vote [in 1948]. They thought [Dewey would] win. I wonder how many Democrats in 2016 didn’t bother to vote.”

(Times of Israel).