Jewish lawmakers say anti-Semitic material removed from controversial bill mandating schools teach courses on ethnicity.

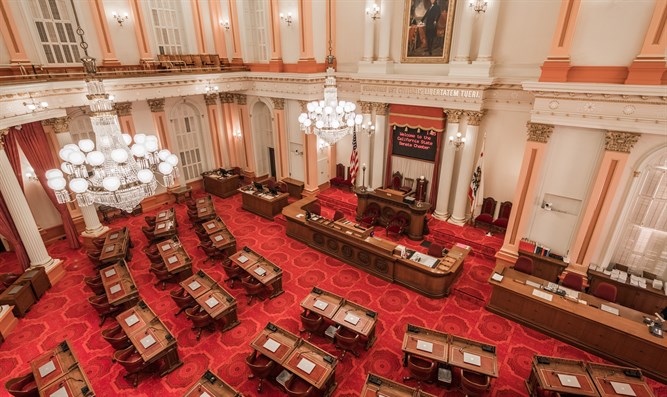

Jewish lawmakers critical of early drafts of an ethnic studies curriculum said they were satisfied with a version of the curriculum that cleared both houses of the California Legislature last week.

The bill mandating ethnic studies would make the state the first in the nation to require the course, which examines race and ethnicity with a focus on people of color.

The liberal California Legislative Jewish Caucus had criticized the original model of the curriculum, introduced in 2019, saying it carried an “anti-Jewish bias.” They and others charged it painted Israel in a negative light, barely mentioned anti-Semitism and included a rap lyric that they said contained an anti-Semitic trope.

Assembly member Jose Medina, the author of the bill to mandate ethnic studies and a staunch supporter of the discipline, also signed a letter condemning the draft (Medina is one of a handful of non-Jewish members of the Jewish Caucus). Gov. Gavin Newsom said at the time that the measure as drafted would “never see the light of day,” and the model was revised.

The revised version of the curriculum, which was approved by the state Board of Education in March, includes two lessons on Jews in California — one on American Jewish identity and another on the experience of Mizrahi Jews, or Jews from the Middle East. It also removed the sections deemed anti-Israel and anti-Semitic.

In a joint statement Wednesday, the Jewish caucus expressed its “sincere hope” that the revised Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum would benefit students across the state, pointing to “guardrail” language that it helped insert into the legislation in order to ease the worries of Jewish groups. That language prohibits discrimination in ethnic studies courses based on religion and nationality — including against Israelis — and prohibits the use of the original draft.

Despite the guardrails, however, a handful of the original drafters of the 2019 curriculum began working directly with school districts to implement ethnic studies courses independent of the statewide version. The model curriculum is expected to be used as a blueprint in schools across the state, but while California “encourages” its use, the legislation also allows districts to use existing curricula or, if they choose, to adopt a “locally developed” course approved by the school board.

The bill now heads to Newsom’s desk.

Although the revised curriculum satisfied some Jewish organizations, including the San Francisco-based Jewish Community Relations Council, others remain fiercely opposed to the bill. In a statement last Thursday, the antisemitism watchdog Amcha Initiative denounced its passage and urged a veto by the governor, arguing it does not do nearly enough to prevent “overtly anti-Semitic” and anti-Zionist content from being taught in classrooms.

The debate over ethnic studies in California has become a flashpoint in the larger national debate over what schools should teach about history and racism in the United States. Supporters say that ethnic studies can paint a more complete and inclusive picture of the experiences of the state’s diverse populations. Opponents charge that such programs teach a version of critical race theory, a legal and educational framework that says racism is built into the country’s institutions, that heightens tension between races and amounts to progressive indoctrination.

Jewish critics of the ethnic studies curriculum see it as a foothold for marginalizing Jews and demonizing Israel.

David Bernstein, founder of the Jewish Institute for Liberal Values, said in a statement, “We have been warning the Jewish community that critical race ideology will continue to give rise to anti-Semitism and anti-Israelism.”