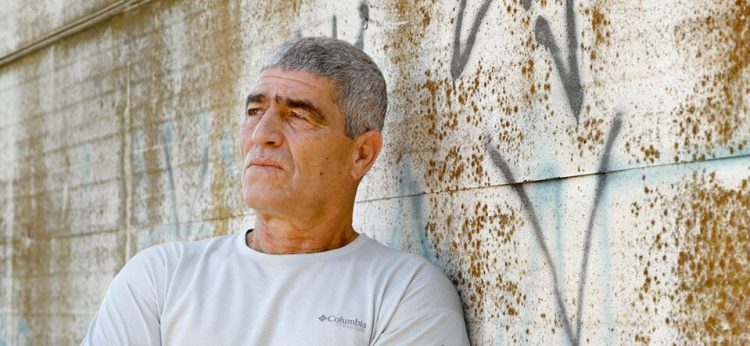

Maj. Gen. (res) Tal Russo is grateful for the relative quiet along the northern border since 2006, but thinks Israel has become “addicted to quiet,” sometimes to its own detriment.

In a special interview with Israel Hayom, Russo praises his former soldier, Naftali Bennett, says former IDF chief of staff Dan Halutz was misjudged, and explains why the Labor party is holding a grudge against him.

In the early 1990s, when he was appointed to command the Maglan commando unit, Tal Russo chose to bring along a few officers from other units to upgrade it. Among the people he convinced to join him was a young officer by the name of Naftali Bennett, who Russo had sent to the officer training course a year earlier.

Almost 30 years later, Russo, 61, a retired major general, thinks about his former subordinate, who would eventually become the prime minister of Israel, with a smile. “I spoke with him after he became prime minister,” says Russo. “I told him I would help him any way he chooses, and I mean it. He’s a talented guy, very pragmatic. He took an all-or-nothing gamble – he’d either lose everything or become prime minister – and he won.

“Bennett is the real religious Zionism in my view, not those who call themselves the Religious Zionist [Party]. He’s been through a process of political maturation, and I believe the systems support him. Unlike [Benjamin Netanyahu], he doesn’t only listen to himself and his own thoughts. He’s assisted by others, and this is important to functioning normally. No one was born to be prime minister.”

Q: What does he need that he doesn’t have?

“The experience, the understanding. But this applies to anyone who would have taken this job now. He got a little basic training as a minister, and that gave him some perspective. I’ve seen prime ministers at work; none of them function perfectly on the first day. The more time that passes without any turmoil and without huge dramatic events, will help him. And of course, he has to consult, listen, and not think he knows everything. [Netanyahu] didn’t have that. He decided everything alone, or with the family.”

Russo’s experiment with political life was short-lived. He joined Labor in February 2019 and his slot on the party ticket was assured by then-chairman Avi Gabbay. He was elected to the 21st Knesset and was an MK for five and a half months until the Knesset dispersed. Gabbay subsequently departed, and Russo decided to retire from politics.

Q: Do you regret that episode?

“Not at all. It was an amazing education for me. At home, I was taught to try making an impact as much as possible. That’s how we were raised. I didn’t go into politics for a career; I went in to effect change. But I discovered something is warped about our politics, where the Knesset is irrelevant and the opposition is irrelevant. The coalition rules so strongly, that if you’re in the opposition you don’t really have the ability to influence things. At least, this is how it’s been up to now.

“I saw MKs who reached their peak by making it into the Knesset, that they were getting respect. The Knesset is truly an incredible place, with a very impressive organizational structure, but the moment I saw I didn’t have an influence, there was nothing left for me there. I suppose the timing and the platform were less suitable.”

Q: The platform meaning the Labor party?

“Yes, the human composition there didn’t fit my mode of thought. People who had been in the Opposition for too long, who enjoyed sitting on the backbenches and just shouting dissent. That position is completely contradictory to my way of thinking, as a person of action.”

Q: Do you regret supporting Gabbay at the time, who was close to joining the Netanyahu government (a move that was ultimately upended by members of his party)?

“Not at all. If we had been in the government, we could have changed things quicker.”

Q: Or Netanyahu would have taken you for a ride like he did to Benny Gantz after the third election.

“It’s true that my confidence was a little shaken when I saw his conduct with Benny, but I think the agreement with us was stronger.”

Q: Was Netanyahu a good prime minister?

“In the beginning, yes. I accompanied him essentially from the moment he entered office in 2009 (when Russo commanded the IDF’s Operations Directorate). At the time, he was far more stately, both in terms of the people he chose to be around him and his attitude toward the security agencies for which he was responsible.

“As time went on, the more he changed. Things became more personal for him. More personal loyalty, more personal devotion. I think after the 2015 election he started feeling like a god. It appears the Americans knew what they were doing by limiting the presidency to two terms.”

Q: Are you still in contact with the Labor party?

“People in the Labor party are angry with me because during the last election I recommended Gantz [as prime minister]. I’m less attached to the people in Labor, but I have a special affection for the [party] from growing up.

“The whole thing with parties these days isn’t serious. They try creating a left and a right here. Before I entered politics everyone spoke with me, from [Avigdor] Lieberman to Yamina, to every other party you can imagine. In the end, you see that 70% of the population in Israel agrees on 90-95% of the issues. There’s almost no difference.”

Q: But [Labor chairwoman] Merav Michaeli did something amazing. She took a dead horse and breathed new life into it.

“Without a doubt, she did that very impressively.”

Q: Will you go back?

“It’s not likely, no. My place is more in the center, and I think there’s still a vacuum in the center.”

Q: Why? Blue and White, Yesh Atid. It’s pretty full.

“Blue and White needs a facelift and to add new blood if it wants to be a large party. Rather than be just another piece in the coalition puzzle. [Yair] Lapid surprised me with his conduct, during the election campaign and after.”

Q: Contrary to many former defense officials, you weren’t mad at Gantz for joining the Netanyahu government.

“True. I thought it was the right thing to do, and I still think that. If Benny wouldn’t have been there, the situation today would be much worse. A lot of the time we criticize the things that did happen and don’t look at what could have happened and was prevented. I think we would have seen many ministers go completely wild if Blue and White hadn’t been there.”

Q: Is there any chance you return to politics, or have you closed that chapter in your life?

“I don’t rule anything out, but it will only happen if I feel I can make an impact. In the Knesset, I had a good relationship with everyone, even the Haredim and Arabs. I was less connected to the shouting culture. When the cameras aren’t around, everyone talks with one another, but the second the cameras go on, everyone becomes very extreme. I’m not accustomed to that culture of debate.”

When Russo enlisted in the IDF, he was among the first to serve in the Israeli Air Force’s elite Shaldag commando unit. Later on, he joined the elite counterterrorist and intelligence gathering unit Sayeret Matkal, then commanded the Maglan commando unit, the 551st reservist Paratroopers Brigade, the 98th Paratroopers Division, and the 162nd Armored Division.

He then served in three general staff positions – as head of the Operations Directorate, GOC Southern Command, and commander of the Depth Corps, formed in 2011 to coordinate the IDF’s long-range operations and operations deep in enemy territory. He removed his uniform four years ago to enter civilian life.

Today, too, he remains close to many in the IDF, mainly from the army’s elite units, along with senior Mossad and Shin Bet officials. They consult with him, keep him in the loop, share their reservations.

In the summer of 2006, on the eve of the Second Lebanon War, Russo was between positions. He had just finished commanding the 162nd Armored Division, done a few projects at IDF headquarters, and was awaiting his promotion to the rank of Major General.

When the war erupted, Brig. Gen. Russo found himself without a defined role and increasingly frustrated. Then-commander of the Operations Directorate, Gadi Eizenkot, tasked him with spearheading the army’s special operations, and in the weeks in which he served in that capacity throughout the war, over 30 such operations in Lebanon were carried out by Sayeret Matkal, Shaldag, the Shayetet 13 naval commandos, and other units.

After the war, he was appointed to replace Eizenkot, who went on to become GOC Northern Command.

“We could have done much more in that war,” says Russo. “If we would have prepared differently, if we would have entered it with the right plans, the results would have been better. We exhausted maybe 15-20% of our capabilities, our maneuvering was just crap. So it’s hard to define the war as a failure because the quiet in the north is a success, and that was the declared objective of the war – quiet for many long years. But we could have exhausted our capabilities much better.

“The first week of the war, before I took command of the special operations, was the worst. I shuttled back and forth between the commanders in the field and saw we still hadn’t made the mental switch to being at war, both within the general staff and the field command. That’s my main lesson learned: You need to flip that switch as quickly as possible. This is something that happens to quite a few commanders, who seemingly see everything clearly, yet still, they can’t think in terms of war.”

Q: That war created our deterrence against Hezbollah, but also their deterrence against us.

“That happened because we became addicted to quiet and imposed restrictions on ourselves. In my eyes, that’s a disaster – to see terrorists enter Israeli territory and then not respond, not to kill them, not to hit Hezbollah.”

Q: When you heard that several terrorists entered Israeli territory next to the Gladiola outpost to kill soldiers and that the IDF spotted them and allowed them to escape, what were your thoughts?

“That it was a mistake. You need to set clear and unequivocal rules. Terrorists who cross the border need to die, period. This isn’t a matter of discussion or judgment. A non-response to crossing the border is, in my view, the most significant loss of deterrence. When you need to start explaining to soldiers why we did that and how we’ve reached such a point, you apparently come to realize this isn’t something that’s acceptable.”

Q: And what message does this convey to Hezbollah?

“They understand how desperate we are for quiet, and it’s not good. The thirst for quiet stops us from doing things we should do.”

Q: Many would argue this is quiet is very welcome.

“The quiet is great, but we can’t let it dramatically impair our deterrence and ability to act.”

Q: Israel should have maintained its freedom to act in Lebanon?

No shouldn’t have, needs to. Israel needed to maintain its freedom of action in Lebanon, certainly when it comes to approaching the border or crossing it. We needed to create more covert means to allow ourselves to do this. And there are solutions.

“Everyone thinks the [so-called] war between the wars began in Syria a few years ago. The truth is it began 15 years ago, but it should have remained more intensive and diverse. Yes, very nice things are still being done, but we need to take many more risks and do more things in relation to Lebanon.

“I don’t think we are deterred against Hezbollah, or to be more precise, I don’t think we need to be deterred from Hezbollah. In the next war, if we work properly, we can get to the point where we annihilate this organization from a military perspective.”

Q; At the cost of sustaining heavy damage.

“Hezbollah can inflict heave damage on us, but from a perspective of proportionality, there’s no comparison between what it can do to Israel and what will happen to it and to Lebanon.”

Q: Do you share the view that Hezbollah’s precision missile project is the greatest threat to Israel, aside from the Iranian nuclear threat?

“No. They still haven’t reached a critical mass that can tip the scales, certainly not if we insert our defensive systems into the equation.”

Q: But this could happen, and the question is whether or not it justifies a preventative strike.

“I don’t believe we’ll carry out a preventative strike one sunny morning. That’s nice in theory, we wanted to do that many times in Lebanon and in Gaza, but it’s not so simple. You need some sort of escalation for that to happen so that the domestic and international fronts are on your side. You do something like that when facing a clear and present existential threat; this isn’t the situation in Lebanon at the moment.”

Q: In the most recent operation in Gaza, we saw what began in the Second Lebanon War – we have a serious problem of perception against the enemy. That even if we win militarily, he wins perceptually.

“No one here deals with perception, only with spokesmanship. Perception is determined through many tools, but we consistently lose on this front because we don’t use the tools properly. I hope this starts changing now.”

Among the operations that Russo commanded during the war was Operation Sharp and Smooth, the largest special forces mission of the campaign in which Sayeret Matkal and Shaldag raided Hezbollah headquarters in Baalbek in the Beqaa Valley. There was another operation carried out by Sayeret Matkal in the southern sector, which resulted in acquiring high-value intelligence, and remains classified to this day.

“There was also the Shayetet’s operation in Tyre, after which, although we didn’t get the target – a senior Hezbollah operative – the organization’s senior leaders stopped appearing in public. And there was a very nice operation carried out by Maglan, codenamed ‘Beach Boys,’ in which the unit, [under the command of current GOC Sothern Command Maj. Gen. Eliezer Toledano], eliminated dozens of terrorists and took out rocket launchers in the Tyre area.”

These operations were improvised on the fly during the war. They were put in motion only after the appointment of Russo, who took control of the issue.

“Shaldag, for example, wasn’t even able to push forward any missions until we started working, and from that point onward they worked almost every night. This requires pre-planning, but more than that – a combination of all of Israel’s security capabilities. The dramatic shift came when everyone worked together.”

“Shin Bet agents participated in the Shayetet operation; Sayeret Matkal carried out missions with the Mossad, members of [the Military Intelligence Directorate’s] Unit 504 joined some of the operations. A lot of combinations of special forces units and special capabilities, which maximized our advantages.

“The problem is that it was improvised. If there had been such a body to begin with, which would have worked and prepared everything in advance, these operations would have ended in far better results. Today, the Depth Corps and other elements are responsible for this.”

Q: Was Dan Halutz a good chief of staff?

“On a personal level, I enjoyed working with him very much. I was the commander of the 162nd Armor Division, which evacuated northern Samaria during the disengagement, and I saw his capabilities.

“Chiefs of staff never come out looking good from all-out war, which is why chiefs of staff never like all-out war. That war fell on him at a bad time, to a large extent, he was its victim. He was wronged because some of the failures weren’t necessarily his fault, mainly in relation to the ground forces. And as stated, in the outcome test, we see today that that war wasn’t as bad as the impression that was given in real-time.”

Q; Do you think an air force person can’t be chief of staff?

“An air force person can be chief of staff, but it’s important that he experiences and holds more positions in the broader army. I’m not necessarily talking about general postings, rather on the lower levels, earlier on. The integration of air force personnel is important, but it’s a process.”

Q: Was Ehud Olmert also wronged?

“Olmert was a significant ray of light in terms of navigating the war and the decision-making process. I worked with him after the war, I saw how he made decisions. For example, throughout the process that led to the destruction of the nuclear reactor in Syria, and it was very impressive. I’m not judging his ethical side. From the perspective of running and managing things, he was one of the better prime ministers, even though he had no background in the [security] domain.”

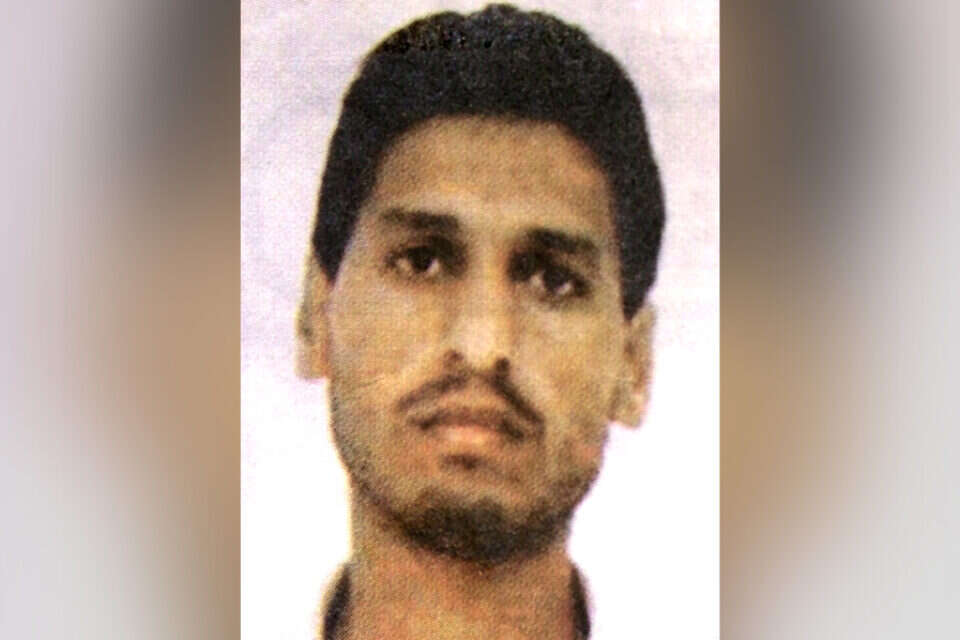

As GOC southern Command, Russo spearheaded Operation Pillar of Defense in 2012. The campaign began with a perceptual victory for Israel – the elimination of Hamas military chief Ahmed Jabari. Israel began Operation Guardian of the Walls from a position of inferiority after Hamas set the narrative by launching missiles at Jerusalem.

“From a capability standpoint, the IDF greatly improved in the years since Pillar of Defense. But the result, this time, wasn’t good enough. We should never have been caught off guard by the opening salvo, and we shouldn’t have let them dictate the developments in the first days of the fighting, which allowed them to achieve the strategic victory of claiming Jerusalem for themselves.

“The situation should have been the opposite: Instead of them threatening us, we should have been threatening them. Let them be scared. Have 100 planes in the air, and tell them that if they dare shoot at Jerusalem, all of Gaza will fall.

“The problem is that we analyze the other side with rational thinking and forget that a lot of the time – even though they have serious people, in the north [Hezbollah] and in the south [Hamas] – they are driven by honor. Personal honor, national honor. Hamas should have had many more casualties. That didn’t happen.”

Q: Maybe we should have started by killing Yahya Sinwar and Mohammed Deif?

“In principle, we make too much out of them. Deif is a desperate, finished, broken person who has nothing to lose. Sinwar has leadership problems internally, as we saw. Even Jabari’s popularity wasn’t out of this world when we killed him, but he was a symbol. And symbols need to be taken out.

“So Operation Guardian of the Walls was a nice sample of the IDF’s capabilities, which also delivered a type of clear message to our surroundings, but the outcome should have been far sharper and clearer.”

Q: The government kept going because it was looking for a win.

“In this regard, too, we need to come prepared. We need to coordinate expectations with the political echelon. We have to invest in discussions and preparations before launching an operation.

“I’ve experienced the pressure of the political echelon when the fighting begins. It’s a type of pressure where if you didn’t prepare them [the politicians] properly, they want things from you that you can’t do.”

Q: In the recent operation, too, the brigade commanders criticized not sending ground forces into Gaza.

“I don’t think conquering territory needs to be an objective. However, we can’t be afraid of that.”

Q: And we frighten ourselves?

“To a certain extent, yes. An atmosphere has emerged where we fear for the lives of our soldiers more than the lives of our civilians. This is disastrous in my opinion. Something within us has become warped: Instead of the soldier protecting the civilian, everyone is protecting the soldiers. Protecting human life is important regardless, but it mustn’t cause the army to hesitate.

“[A ground operation] has immense significance because it creates deterrence and creates targets. There’s no need to conquer all of Gaza, but if there are measures we can take that serve us – we need to implement them.”

Q: The fear is over casualties and soldiers that fall into the enemy’s hands.

“But it also generates damage to the enemy. Exponentially. We put our soldiers at risk but put [the enemy’s people at risk times a thousand.

“I’m not in favor of a fair fight. I’m not talking about some Bill Carter western – a duel between one of our fighters and one of their fighters to see who draws first. I’m in favor of killing 1,000 of their fighters for every one of ours. If you’re going in to conquer a certain area, rip it to shreds.

“The operation in Gaza is not without its accomplishments. The investment in defense – mainly in the new underground barrier – has proven itself and prevented all attempts to cross the border. Iron Dome, too, has done an excellent job. The bottom line, Hamas wasn’t able to carry anything out. What I found missing, though, was an offensive facet, and not in the context of infrastructure targets.”

Russo believes Israel needs to change its policy against Hamas. “The entire subject of cultivating Hamas in recent years is problematic. When I left Southern Command, Hamas was an enemy. We did everything through the Palestinian Authority. Netanyahu, to weaken the PA, strengthened Hamas. He gave them direct money, which you can’t control. This has been a net negative for us. The PA is weaker, Hamas is stronger, and we don’t know where the money went.”

Q: It was a mistake to give them suitcases full of cash?

“Certainly in the way it was done. It should have been done through elements that can monitor where the money goes.”

Q: So what needs to be done now?

“We need to reach some sort of arrangement, but through the PA. Through the Europeans. Through the United Nations. We can help with humanitarian projects, rehabilitation, but the problem of Gaza we probably won’t solve.

“When they asked me to be GOC Southern Command, I preferred the north. Things are simpler against Hezbollah: There’s an enemy, and that’s that. In Gaza, things are far more complex. After all, you won’t kill two million people, and you don’t want to destroy Gaza. Even toppling Hamas isn’t discussed here.”

Q: And this should be discussed?

“I don’t think Hamas can be toppled without occupying the Gaza Strip for two years. But we need to work to weaken Hamas, target its leadership, its clerks, all its systems. To separate it from the people. To bring projects and work and housing to the civilians, and at the same time hurt Hamas.”

Q: What do you think of the saying that hitting Sderot should be the same as hitting Tel Aviv, and that every balloon should be treated the same as a rocket?

“You can say you’ll launch an all-out war over everything, and that’s what that saying implies. Anyone who knows this sector and this enemy knows there will be random shots fired. You need to make sure there are far fewer of these random shots than in the past, that you have strong deterrence. It would be better if there were zero, but that isn’t practical.”

Q: So why not hit them hard for every one of these random shots?

“You can hit them hard, the question is how hard.”

Russo is of the view that Israel must work to resolve the matter of its captive and missing soldiers and civilians in Gaza. He reveals that throughout his entire time as head of the Operations Directorate, despite the countless operations and efforts, Israel was unable to formulate a clear picture as to the whereabouts of former soldier Gilad Schalit, who was held by Hamas in Gaza.

“That taught me how hard it is to generate intelligence inside Gaza, in the most crowded place in the world. After Gilad returned home, we tried scrutinizing, to understand if we could have reached him another way. We understood we didn’t have good enough intelligence for any [rescue] operation.”

Q: So we are handcuffed to prisoner exchange deals for which we will forever pay an insane price.

“As painful as it is, one can’t equate a living IDF soldier in enemy hands to the bodies of two soldiers, and two civilians, one of whom is mentally ill who crossed the border. Yes, there’s a difference between a living soldier and a body. You can and should pay a price sometimes, but what does “we’ll do anything” mean? We’ll conquer Gaza? Sit there for two years going door to door looking for them? We’ll open the prisons and free all the murderers? That’s not serious.”

Q: So the State of Israel won’t do everything it can?

“Israel needs to do what’s possible, within the bounds of reason.”

Of all Hamas’ achievements during Operation Guardian of the Walls, Russo is most troubled by the connection it forged with Arab Israelis amid the backdrop of violence in the mixed cities. “It happened too quickly, and too great an intensity. We need to address this today because in future military campaigns it will be even more difficult to handle.”

Q: What would you do?

“First of all, continue with the effort, which began too late, to locate the rioters together with the Shin Bet. We need to reach everyone, anyone who participated in the violence; the Jewish rioters as well. Arrest every single one of them.

“The second thing I’d do is launch operations to collect illegal firearms. Take a village or suburb of a city, and strip it clean. Just as we did against Palestinian terror. We need to use the Shin Bet, investigations, do everything possible. Otherwise, in the next war, reserve soldiers won’t want to go fight, because they will need to defend their families [at home]. I’ve already heard people say this.

“We need to dramatically reduce the number of weapons in the Arab sector, the crime. Not everything there is nationalistic. Anyone who senses anarchy goes out with a rifle. I’ve visited the unrecognized Bedouin communities [in the Negev]. We met some kid and asked him what he wants to be when he grows up. He answered: ‘I want to have a job, and I want to make money, to buy an M-16 [rifle].’ That’s his dream, to make money to buy a rifle.”

(Israel Hayom).