Tel Aviv and Harvard University scientists have created and linked up nine Organs-on-a-chip, including brain, heart and liver, paving way for personalized drug development

By SHOSHANNA SOLOMON

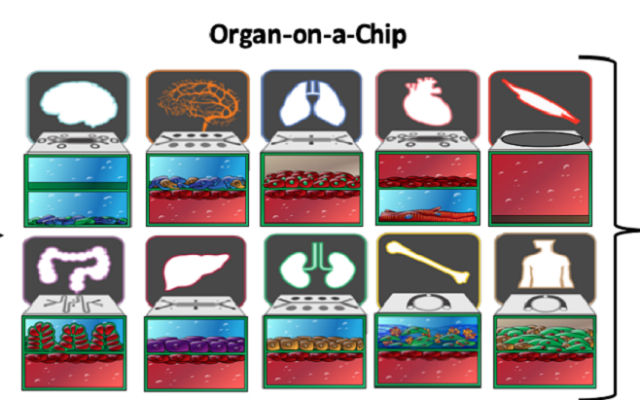

In what sounds like something straight out of science fiction, Israeli and US researchers say they have created nine different mini human Organs-on-a-Chip that will pave the way for researchers to test out drugs as if on humans. Not only that: the researchers also managed to connect the nine Organs-on-a-Chip they have developed — including a Brain-on-a-Chip, a Heart-on-a-Chip and a Liver-on-a-Chip — creating what they call a “mini Human-on-a-Chip.”

Two new studies by researchers in Tel Aviv University and Harvard University on the subject were published in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering on Monday.

Organs-on-a-chip were first developed in 2010 at Harvard University. Then, scientists took cells from a specific human organ — heart, brain, kidney and lung — and used tissue engineering techniques to put them in a plastic cartridge, or the so called chip. Despite the use of the term chip, which often refers to microchips, no computer parts are involved here.

What is new in the two studies published on Monday is the fact that the researchers have now managed to link-up the various organs, and have proven that these can react to drugs in the same way as human organs would in a clinical trial, said Dr. Ben Maoz of Tel Aviv University’s Department of Biomedical Engineering and Sagol School of Neuroscience in an interview with The Times of Israel.

When developing drugs, researchers try them out first on rodents and only then, if successful, on humans. But some 60%-90% of the drugs that are successful in rodents fail in humans, explained Maoz, a co-author of the studies.

This makes the process of drug development very long and expensive, he said. Ideally one would want to cut out the rodent stage and get to human testing directly, for quicker results. That of course is impossible. Until the two new studies.

Indeed, a team of 57 scientists at Tel Aviv University and Harvard and other research entities and drug developers, worked for seven years on a project to develop what they call “a functioning comprehensive multi Organ-on-a-Chip (Organ Chip) platform” that reacts to drugs just as real humans would react to them in a clinical setting.

“We created a human model that is not a human being,” said Maoz, who co-authored the studies on the subject with Prof. Donald Ingber, the founding director of Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, and with the Wyss Institute’s Prof. Kevin Kit Parker.

The scientists did this by taking human cells and through tissue engineering managed to mimic the functionality of the organ from which the cells were taken — like the liver or the heart — within a plastic cartridge the size of a USB flash drive.

The kidney acts as a filter, and the heart acts as a pump in the body, Maoz explained. So the researchers managed to tissue engineer the human kidney cells to work as a filter within the plastic cartridge, creating a “Kidney-on-a-Chip,” he explained. Likewise, for the heart. The scientists managed to make the human heart cells contract within the cartridge, creating a Heart-on-a-Chip. And the same procedure was performed on other organs and parts: the liver, the brain, the blood brain barrier, the lung and bone marrow, skin, and the intestine.

Not only that. The scientists created a so-called Interrogator, a robotic liquid transfer device to link individual “Organ Chips” with each other, in a way that mimics the flow of blood between organs in the human body.

“We created a unique machine that connects between the nine organs, the brain, the lung, the bone marrow, and others, like a ‘lego,’ to create a mini ‘Human-on-a Chip’,” Maoz said. The linking system they created was tested successfully for at least three weeks, the Tel Aviv University said in a statement.

The researchers then tested their Organs-on-a-Chip with two drugs: a drug to combat intestine inflammation and a cancer drug. Their study showed that when the drugs were injected into the new system, the Organs-on-a-Chip reacted and responded to the medications just as real human organs did in clinical trials with the drugs.

“We were able to create nine unique human organs [on a chip] and connect between them and show that what you put in the system is comparable to human clinical data,” he said.

To get to this point was not easy and there were “many challenges on the way” that had to be overcome, Maoz explained. For example, real human organs live off oxygen supplied to them by human blood. So the researchers had to develop a way to feed their cells in a chip and devised an artificial blood — made-up of different chemicals, minerals, vitamins and hormones and other components, that fed the cells in the chip.

Also, whereas in a human organ there are billions of cells, the Organ-on-a-Chip just has thousands of cells — so the researchers had to develop computational models to overcome the size problem and ensure that the cells function like those in a real organ, even while on the chip.

So, what now? “There are millions of directions we can take this,” Maoz said by phone. “Hopefully one day people will be able to use this to test drugs instead of animal models,” he said, serving as an alternative to animal experiments and cutting back on their suffering. Another application could be to use the system to create personalized mini Organs-on-a-Chip — each person with their own cells and organs, to test how they would react to a particular drug.

“We could create a ‘mini me-on-a-chip’,” he said. This would help save time and pain of experiments. “The dream is to expedite and personalize drug development.”

The multidisciplinary research project was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) project at the Wyss Institute. Several authors on both studies, including Prof. Ingber and Prof. Parker, are employees and hold equity in Emulate, Inc., a company that was spun out of the Wyss Institute to commercially develop Organ Chip technology, the universities said in a statement on Monday.