It was music to the ears of Southern Californians.

Raindrops tap-danced on the ground and plinked across rooftops as a powerful storm that drenched the northern part of the state over the weekend moved south.

Powered by an unusually fierce atmospheric river, rain seeped into California’s parched soil and began filling depleted reservoirs. Fire risk in areas that were recently ablaze plummeted in the first significant rain to arrive in seven months.

Parts of Northern California saw deluges of 5 to 10 inches, smashing records from Sacramento to Blue Canyon in Placer County.

And up to 1.5 inches of rain could fall over Los Angeles County by the time the skies clear.

But the relief is tempered by a longer-term reality: After the storm passes, the drought plaguing much of the state will still be here, experts said.

“It’s been very, very dry for two years,” said Jay Lund, director of the UC Davis Center for Watershed Science. “One storm does not end that kind of a drought.”

Bill Patzert, a retired climate scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, sounded an even stronger alarm, warning that one rainy winter would not be enough to pull the state out of its desiccated condition.

He estimates it would take 17 years of above-normal rain and snowfall to refill Lake Mead, an important water source for the West and Southwest, which has fallen to critically low levels.

“There’s no quick fix to the drought,” Patzert said.

Though there’s broad consensus among climate experts that the drought isn’t going to vanish, long-range forecasts show there might be movement — for better and worse, depending on the region.

A tale of two Californias could emerge this winter, with seasonal forecasts showing diverging fortunes for northern and southern parts of the state, with the former seeing a potential improvement in drought conditions while the latter persists in a holding pattern or even worsens.

A major factor driving the potentially divided fate for Northern and Southern California is the emergence of La Niña conditions for a second year in a row, though various factors are used to develop the forecast.

La Niña, essentially the opposite of the warm and wet El Niño climate pattern, is characterized by below-average sea-surface temperatures in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific.

Currently “we’re in a weak La Niña phase,” but it’s expected to become moderate to strong in November or early December, as ocean temperatures become even cooler, said Mike DeFlorio, a research analyst with the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, a department of UC San Diego.

The phenomenon is associated with warmer, drier winters in the Southwest, and colder, wetter conditions in the Pacific Northwest. Northern California, smack in the middle, is more of a toss-up.

South of the Bay Area — throughout Central and Southern California — “prospects for any drought improvement are slim,” said Brad Pugh, a meteorologist with NOAA.

Northern California on the other hand could record anything from near-normal to below or above-average precipitation this winter, though “extreme northern” regions are expected to benefit from the La Niña bump, Pugh said.

Historically, “there isn’t much of a signal” for how the presence of La Niña impacts Central and Northern California, DeFlorio said. “We really only see that historical pattern show up in the Southwest, where there’s more of a signal, more of a chance, for below-normal precip.”

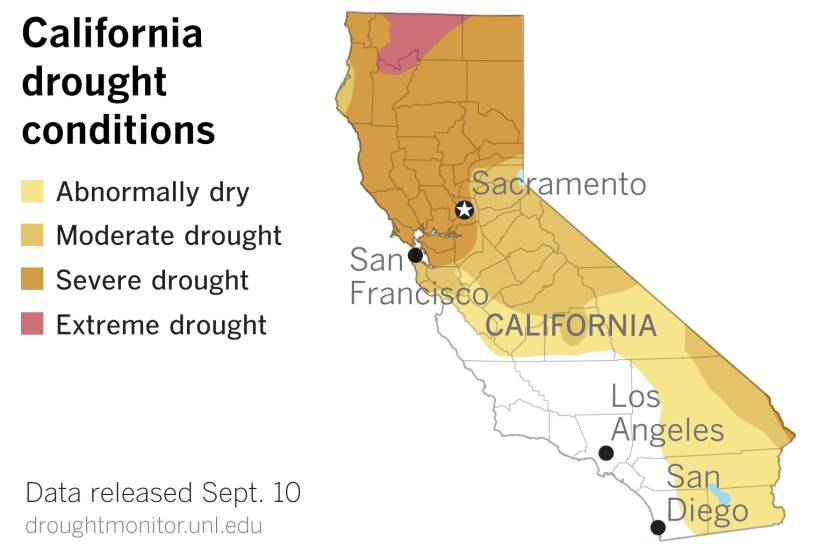

The drought is most severe across Central and Northern California, where large swaths are in extreme or exceptional drought, the second-highest and highest levels, respectively, according to the recently updated U.S. Drought Monitor. Southern California, which is not faring much better, could see areas slide into more dire conditions, while the north improves — if the seasonal forecast turns out to be accurate, weather officials said.

DeFlorio cautioned that the seasonal forecasts, such as the one released by NOAA, show “the dice are loaded one way or another.” They’re frequently based on factors like sea-surface temperature and historical data, rather than short-term weather information. Storms can break through and potentially disrupt the weather predictions.

Still, given that La Niña events tend to coincide with drier-than-normal winters for Southern California, the news is not promising.

Meanwhile, there are some immediate impacts of the current storm — also for better and worse. Heavy rains triggered flood warnings and watches in burn scars up and down the state, including the area charred by the recent Alisal blaze in western Santa Barbara County.

When Lund, of UC Davis, arrived at his office Monday morning, a ceiling tile loosened by a leak had collapsed on his desk — a first for the professor.

Beyond the havoc, there are small blessings. Rain in the Southland will scrub the dust off trees and buildings that haven’t seen significant moisture in more than half a year. The skies will be “crystal clear,” and an “instantaneous greening effect” will follow, Patzert said.

“It’s like an extreme makeover when you get an inch of rain in Southern California,” Patzert said.

Source: LA Times