By Menachem Posner Chabad.org

The trip from Moscow to Tula was fraught with danger, but the prospect of arrest was nothing new to the duo, each of whom had suffered greatly at the hands of the Communist party and their lackeys for their steadfast fealty to Judaism.

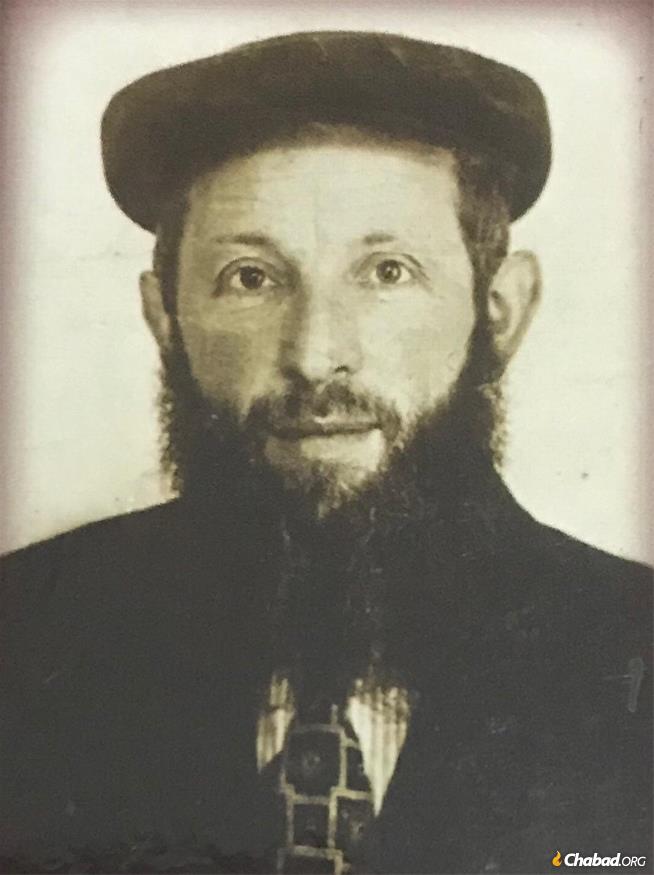

Rabbi Aharon Chazan (1912-2008) and his son-in-law, Rabbi Moshe Sheiner, were stalwarts of the Chabad Jewish underground that spanned the Soviet Union. Living outside of Moscow, they were part of a small core group of chassidim who maintained a secret mikvah, an ad hoc synagogue, and even a matzah bakery in the Chazan home.

It was 1966 when they heard the sad news that the synagogue in Tula had been shuttered, the building slated to become a club. They could never know that more than 50 years in the future, Rabbi Zev and Irina Wagner would move to the city and revive Jewish life there. All they knew was that Torah scrolls languished in a damp and dark cellar of a building soon to be overrun by the godless Soviet authorities.

They knew that the Torahs were technically considered state property and that tampering with them could result in the harshest punishments. But they also knew that Jewish tradition considers a Torah scroll almost like a human being, and that there was no way they could leave the Torahs to be destroyed or defaced.

When the pair arrived in Tula, they were pleased to discover that the local Jews had arranged for the government-appointed guard to look the other way just long enough for them to enter the deserted building.

Descending the dark stairwell, they were greeted by a most shocking scene: Torah scrolls, prayerbooks, and Talmuds lay on the floor, amid broken furniture, castaway cartons and long discarded religious articles.

But this was no time to mourn. They had a task ahead of them. As much as they wished they could take all the holy articles with them, they needed to be selective. Assembling all the Torahs together, they quickly inspected them to see which were in the best condition. They selected two scrolls, whose script still appeared fresh and strong, and loaded them into a large suitcase they had brought for this purpose.

Reentering the sunshine, the two lugged their precious cargo to the station, where they hoped to find a bus to Moscow.

To their dismay, they learned that the next bus would only depart in several hours, which would leave the two bearded men with a suspicious looking package vulnerable to inspection during their wait. To make matters worse, they noticed a police station directly across from the train station. It seemed inevitable that they would be stopped, questioned, and searched.

But years of dodging the Soviet authorities had taught the chassidim to think quickly.

“Come,” Rabbi Aharon told his son-in-law, “Let’s not wait for the police to come to us. Instead, we’ll go to them.”

“Excuse me sir,” they said to the officer on duty, as they entered the police station, “We are strangers here and have several hours until our bus arrives. Do you mind watching our suitcase for us while we take a few hours to enjoy the sights of this city? We will pay you well for your time.”

The policeman gladly took the package and the pair slipped away until right before the bus was to depart. Upon their return, the officer gladly returned their luggage, and the relieved rabbis carried it with them onto the waiting bus.

That same year, Rabbi Aharon and some of his children received permits to leave the Soviet Union. The trip over the border was by rail, and among the limited clothing and personal items they were able to take, the Chazan family packed two Torah scrolls, one of which was from Tula. The rollers were removed, and the two Torahs were combined into one large roll, which was hidden in an oversized pillow.

Thankfully, the border patrol suspected nothing, and upon their arrival in Israel, the Torahs were given to a trained scribe for inspection and repair. The Tula Torah was found to be in extraordinarily good condition, as beautiful and crisp as the day it was written.

Today, the scroll from Tula is used regularly in a synagogue in central Israel frequented by members of the Chazan family. And every Simchat Torah, even though the Tula Torah is heavier than many of the others housed in the ark, the congregants eagerly await their turn to dance with it—uniting with generations of Jews, past and present, who cherish the Torah more than life itself.

Adapted from a story in Sichat Hashavua 1555 with additional information from the Chazan Family.