Day before surprise attack, the IDF intel chief received a report Soviet nationals were fleeing the area ahead of an impending assault — and didn’t tell anyone for over 10 hours.

Nearly 24 hours before the Egyptian military launched a surprise attack on the Israel Defense Forces from the Sinai Peninsula on October 6, 1973, the head of Military Intelligence received a warning that Cairo and Damascus were poised to carry out just such an assault. For over 10 hours, that dire warning, which had the potential to change the course of the conflict, was kept from the government.

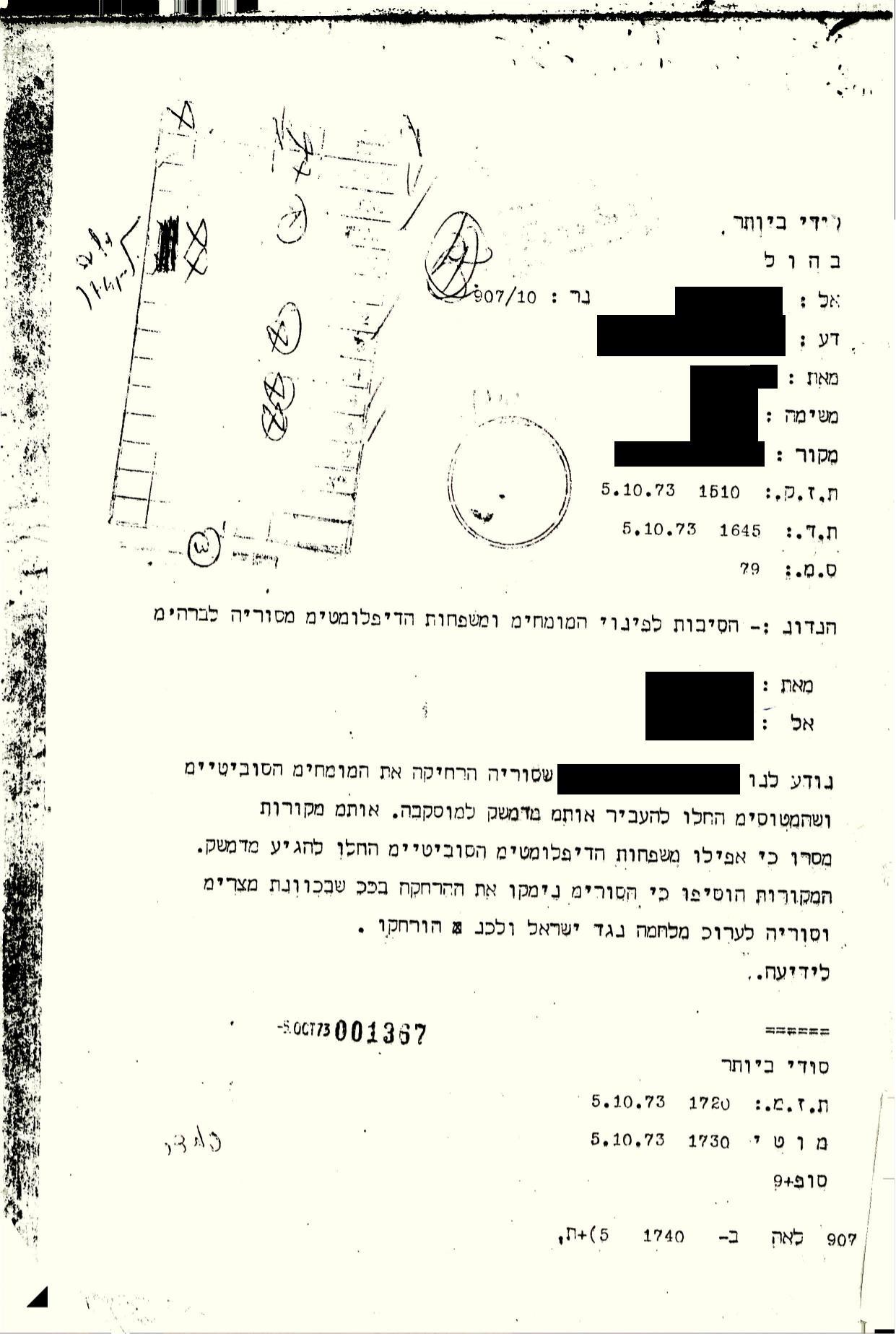

On Thursday, the Defense Ministry archives declassified the urgent warning — known as the “golden message” — as well as the intelligence report based on it that was eventually released to the government, along with the heated exchanges after the war between the then-head of Military Intelligence Maj. Gen. Eli Zeira, who made the decision to withhold the communique, and the Agranat Commission, which investigated the government and military’s failures to anticipate and prepare for the conflict.

The declassification of these documents on Thursday, coming ahead of the 47th anniversary of the war, sheds fresh light on what had been known by the IDF and Military Intelligence before the outbreak, as well as the finger-pointing that came after it.

Following the war, Zeira received the lion’s share of the commission’s blame for Israel getting caught off-guard by the Egyptian and Syrian attacks, allegations that he immediately rebuffed and — now a nonagenarian — continues to reject. In his letters to the Agranat Commission, he maintains that it was the government and civilian leadership that bore the blame for not anticipating the attacks and indicates that he did not immediately pass along the “golden message” because he was waiting for better-sourced intelligence.

The records released this week show the military and the government’s failure of imagination, their hubris and their unwillingness to revisit underlying, foundational assessments — namely that Syria and Egypt were not prepared for another war — in the face of new information.

In the days preceding the war, the military was at its highest level of alertness. In the south, the IDF had spotted the Egyptian military moving unprecedented numbers of troops and weaponry near the border, and in the north, there was also an “unparalleled Syrian military build-up along the front line,” according to Chaim Herzog, an IDF major general during the war who authored a seminal history of the conflict, “The War of Atonement.”

But Military Intelligence and its commander Zeira believed that war was unlikely, that the Egyptians were only preparing for an exercise and that the Syrians were flexing their muscles after the Israeli Air Force shot down a number of Syrian planes in mid-September.

While the IDF saw another conflict with Egypt and Syria as a matter of when, not if, Zeira was convinced that the chances of an imminent war were “lower than low,” as he told an IDF General Staff meeting on October 5.

This assessment should have changed. Later that day, at 4:45 p.m. — just over 21 hours before the Egyptian surprise attack known as Operation Badr that kicked off the war — Military Intelligence received the “golden” communique. The laconic four-sentence message, marked “urgent,” explained the reason the IDF had noticed that Soviet military advisers and diplomats to Syria in the previous days had begun leaving the country, en masse, along with their families. Even now, nearly 50 years later, portions of this message remain classified, including the names of who sent it and who received it.

“It is known to us [redacted] that Syria is expelling the Soviet experts and that the planes have begun taking them from Damascus to Moscow. Those same sources say that even the families of Soviet diplomats have started to arrive from Damascus. The sources add that the Syrians explained the expulsion as being because of the intentions of Egypt and Syria to wage a war against Israel and that they are therefore being expelled. For your information,” the message read.

At the time the message was received, the IDF had also seen a similar mass exodus of Soviet advisers and their families from Egypt and all Soviet ships leaving Egypt’s Port Said and Alexandria. According to Herzog, the military was puzzled by the departures at the time, not sure if it signified a potential split between Moscow and the two countries or if the Soviets were “aware of the possibility of an Arab attack.”

This missive firmly indicated the latter, that an assault was imminent. Yet the “golden message” was not passed on. The officer who received the communique “recalled that the head of his shift told him that evening that the head of intelligence ordered that they not release [the telegram], and to hold it up,” according to the Agranat Commission.

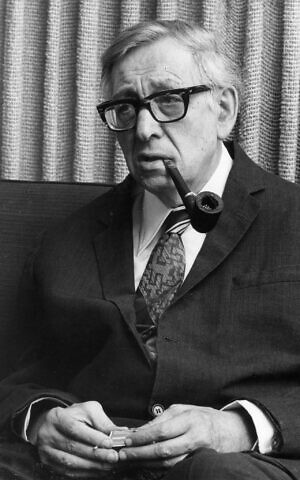

February 1973. (Roni Frenkel/Defense Ministry Archives)

In his response, Zeira never admitted to giving the order, saying he did not remember the incident nor did he think he needed to personally approve its release in the first place.

“But in retrospect, I can try to reconstruct a possible explanation for delaying [its release] with the fact that — as was said — we did not assess that the message added anything to our existing assessment and it’s possible I hoped to receive more significant messages shortly. But as I said, I don’t remember delaying [its release] before midnight,” he wrote to the commission on March 21, 1974.

Indeed, a number of additional reports did come in throughout the night, indicating the precise number and types of aircraft shepherding the Soviet officials and their families out of Damascus and Cairo.

The next morning — the morning of the war — at 6:35, Military Intelligence distributed its report to the government, warning of imminent attack, citing a source in the Soviet Union, whose name remains classified. The intelligence report also apparently included information provided by a Mossad source — Ashraf Marwan, a confidant of then-Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, known by the code name “The Angel” — who warned there was a “99 percent chance” that the war would be launched on October 6, according to Mossad documents released by the state archives in 2018.

At 2 p.m., 7.5 hours after the Military Intelligence report was released, the Egyptians and Syrians launched their surprise attacks on the Suez Canal and Golan Heights, respectively, sparking the 19-day war, which left over 2,500 Israeli soldiers killed and thousands more wounded. The war — and the country’s failure to anticipate it — shattered the public’s trust in the military and the government, along with Israel’s feelings of invincibility following the unexpected, overwhelming victory of the Six Day War six years prior.

(Ze?ev Radovan/Defense Ministry Archives)

The Agranat Commission was formed weeks after the war ended, charged with investigating the myriad failures that allowed such a surprise attack.

The commission’s exchanges with Zeira were also released on Thursday, in which the panel detailed the ways in which the intelligence chief had failed to foresee the attacks.

Though Zeira acknowledges that he made some mistakes, he roundly and vigorously rejects two of the commission’s findings: that he told the government he could anticipate the “intentions” of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and Syrian president Hafez Assad and that such assessments were his responsibility alone.

Zeira maintained that he had assured then-prime minister Golda Meir that he would be able to track the “preparations” for war by Egypt and Syria, during a meeting with the premier on April 18, 1973, but made no such promises regarding the countries’ “intentions.”

“There was a promise about giving a warning about preparations, not about intentions,” he told the commission.

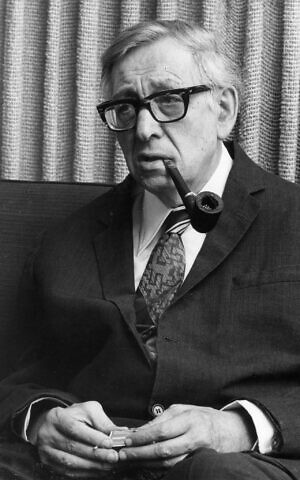

Gonen during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, visiting an IDF command post in

the Sinai Desert. (Yitzhak Segev/GPO)

“To the best of my knowledge — and I am using this language out of caution and responsibility — I did not promise to give a warning in advance about the enemy’s intentions,” he added.

Moreover, Zeira said, such assessments were not his to make, at least not his alone.

“I ask you: Who is it whose training, experience, duty and responsibility require him to determine the intentions of heads of neighboring states, is it the premier of the State of Israel and their top ministers or just army officers?” Zeira wrote to the commission.

“Is it possible to claim that assessing the intentions of heads of friendly countries is the responsibility of the government and that assessing the intentions of heads of enemy countries is the responsibility of the army?!” he asked.

While Zeira was found to be principally responsible for the intelligence failure of the war, the government did not fare well. Golda Meir resigned as prime minister, as did Moshe Dayan as defense minister. Though the Labor party retained control of the government in the election immediately following the war, it lost to the right-wing Likud party in the subsequent election, in part due to lingering disaffection from the Yom Kippur War.

(Times of Israel).