Kfir Damari, SpaceIL’s co-founder, talks about the “Beresheet” mission, plans for “Beresheet 2,” and his hope to spark children’s interest in space.

(January 18, 2022 / Israel21c) I expected the office of SpaceIL—the company that created “Beresheet,” the first-ever private spacecraft to attempt a moon landing, in 2019—to be in an industrial zone, filled with highly classified, space-age robotics. Instead, it’s in an ordinary office building, next to companies geared to earthly pursuits like home decorating and teeth whitening. The only hint of the company’s higher aims is in the office’s modest conference room, where there is a scale replica of the four-legged “Beresheet” craft.

Next to the model, Kfir Damari, co-founder and deputy CEO of SpaceIL, looked huge—and also proud, as if he and his two co-founders, Yariv Bash and Yonatan Winetraub, had just built a complicated LEGO set.

Only three other countries have landed spacecraft on the moon: Russia, the United States and China. It boggles the mind that Kfir Damari, a soft-spoken 39-year-old with reddish hair, a thick beard and glasses befitting Clark Kent, along with a small team of engineers and scientists, had attempted to make Israel the fourth.

“You almost made it,” I told him.

“We are the fourth to land on the moon,” Damari corrected me gently. “We might have had a crash landing, but we got to the moon. A lot of people don’t realize this. We got there.”

To the moon with the UAE

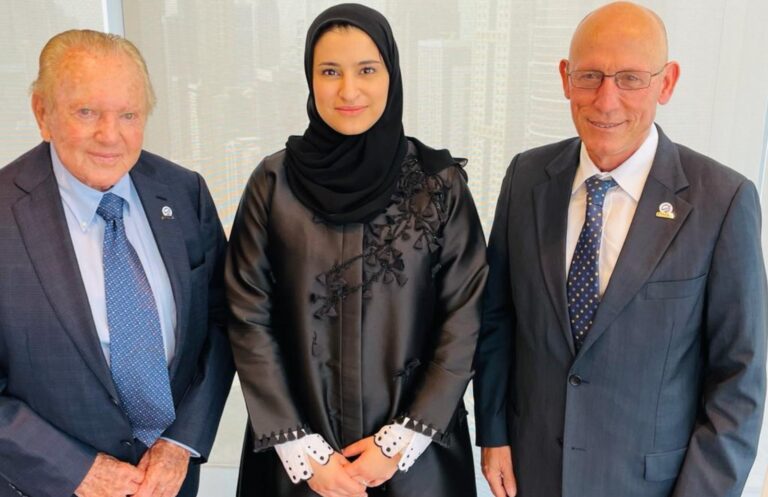

In October, the United Arab Emirates signed a cooperation agreement with Israel to work on space exploration and “Beresheet 2.” The goal is to launch sometime in 2024 or 2025.

The new spacecraft, to be built on a budget of $100 million, will drop one lander on the light side of the moon and another on the dark side, where only China has ventured. After dropping off the landers, the ship will orbit the Moon for two years.

During that time, Damari said, it will serve as an educational platform for children around the world. “Beresheet” had engaged 2 million children, half of them in Israel, in the space project. He hopes that the new craft will inspire adults and children in the United Arab Emirates, Europe and Africa to create bonds with Israeli peers.

“For Israel to lead the mission and for children to do their first steps of engineering and space exploration through Israel will be amazing for Israel’s image,” he continued. “I believe that when children from other countries will work with Israeli children on projects it will also shape their perspective.”

Damari added that the “Beresheet 2” project is not only aimed at children interested in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) subjects.

“Can you imagine the kinds of art projects that can be done with a platform orbiting the moon?” mused Damari. He added that the Israeli Education Ministry is already planning curriculum ideas for students from kindergarten through high school.

“For me, this is making something impactful for Israel,” he said. “It also shows how all of us can reach for something impossible and make it possible.”

Passengers in the space capsule

With a budget of $100 million, “Beresheet” was the thriftiest spacecraft ever to enter lunar orbit. It was not much taller than a kitchen counter at 5 feet by 7.5 feet, so it didn’t have a lot of room for fuel.

The engineers planned for the spacecraft to hitch a ride on the Earth’s gravitational field after takeoff from Cape Canaveral, Fla., on Feb. 22, 2019. It journeyed in elliptical orbits around Earth until it glided into the moon’s gravitational field on April 4.

A week later, it began its descent toward a volcanic field called the Sea of Serenity, close to where the Apollo 17 astronauts landed in 1972. Only 8 miles from the surface of the moon, it began slowing down, preparing to land. Although hardware malfunctions prevented “Beresheet” from making a soft landing, land it did.

Along with the lander, which is still on the Moon’s surface, are some souvenirs from Earth, including thousands of human faces in photographs taken next to the replica of the “Beresheet” craft that stood in the Duty-Free Shop at Ben-Gurion International Airport for about five years.

“Me and my family and all my Facebook friends are on the moon,” said Damari. “The goal was for them to be passengers in the space capsule, and digitally they were.”

The photos are preserved in a few magnetic discs along with optic disks that “don’t need a reader, only a microscope.”

“Do you think there is someone who will be able to see them?” I asked.

“I can’t say if there are other civilizations out there in the universe,” said Damari. “If there are, it will be great if they come and see everything we left on ‘Beresheet,’ including 15,000 books in 37 languages, all of Wikipedia, drawing and blessings of kids.”

“I can’t promise that aliens will read all of it, but I’m certain that our kids and grandkids will have the opportunity,” he added.

Also on board was a miniaturized copy of the Hebrew Bible. In fact, the first word of the Bible is beresheet, meaning “in the beginning.”

The spacecraft’s name was chosen via a Facebook vote.

“I don’t know who suggested it but the name connects us to the past and to the future. It was Israel’s first spacecraft, but not the last,” said Damari.

SpaceIL ambassadors

Since the start of SpaceIL, volunteers have served as its ambassadors, traveling around the country to speak with students and adults about the space mission. There are still about 130 volunteers giving lectures in Israel and abroad.

“The volunteers go to Arab, Ethiopian, religious communities,” he said. “They want to talk to everyone about space.”

He related that one volunteer spoke at a school in Herzliya seven years ago. Recently, SpaceIL received a thank-you letter from a boy who said he had known nothing about space. The volunteer’s talk inspired him to build a nanosatellite.

“This is a new space age, with new technology,” said Damari. “People can now build small, cheap satellites such as Nanosats and Cubesats.” Some of SpaceIL’s volunteers have even changed careers to go into space research.

“We are connecting as many people as possible to space,” said Damari. “I look forward to having girls from the United Arab Emirates doing space projects with girls from Israel.”

When SpaceIL began in 2010, studies showed that the number of STEM majors in Israel was decreasing in proportion to the population. Since “Beresheet,” it has increased. “We hope to keep increasing the numbers of STEM majors from all sectors,” said Damari.

However, he doesn’t push his interests on his two children—Omer, 8, and Maayan, 5. They traveled with him and his wife Dotan to the 2019 launch at Cape Canaveral, “but I want them to find their own dreams,” he said.

Dotan, an occupational therapist, works with children on the autism spectrum. “She’s changing the world one person at a time,” said Damari.

A creative child

I asked Damari about his own childhood.

“My parents bought me a clone of an Apple computer when I was six,” he said.

“The computer was missing components so all I could do was to create programs. I wrote a program to play Tic-Tac-Toe. I created a virus. I was always looking for other challenges,” he said.

After high school graduation in 2000, Damari was accepted into the Israel Defense Forces elite Unit 8200.

“I became an officer, then studied physics and space engineering at Ben-Gurion University,” he said. “In 2010, when I was teaching, Yariv Bash, an acquaintance, posed a question on Facebook. Yariv asked, ‘Who wants to go to the moon?’ ” Damari recounted.

Bash, an engineer, was inspired by the Google Lunar X Prize, an international competition offering $20 million to anyone who could land a probe on the moon.

“I asked Yariv, ‘Are you serious?’ and he said he was.”

Yonatan Winetraub, also an engineer, Bash and Damari met at a bar in Holon, a small city south of Tel Aviv.

Their first idea was to launch a small bottle into space. When they realized they needed more equipment, and more money, they raised funds and joined forces with Israel Aerospace Industries, which eventually built the craft.

Although the $20 million Lunar X Prize was never awarded, SpaceIL received its $1 million Moonshot Award.

An underfunded startup

Damari said that compared to other countries’ space programs, SpaceIL is relatively small, underfunded, and operates more like a startup than a national space initiative.

About 40 people worked on the first mission. There are currently 20 employees. SpaceIL has raised $70 million, mostly from three main donors: the Patrick and Lina Drahi Foundation, the Moshal Space Foundation and philanthropist Morris Kahn, who announced after the “Beresheet” crash landing, “We will complete the mission.”

SpaceIL is now raising additional funding for its next mission, along with the money needed for the craft that will orbit the moon for at least two years. Damari hopes that international partners will pitch in.

“We are not yet sure where we’ll launch from, but we will be given a window of six months, so we need to be ready,” said Damari.

“Would you also like to go up into space?” I asked.

“I would love to see Earth like a small marble,” he replied, adding that new technologies will soon make it possible for people to have that experience.

But he confessed he disappoints people because his background is engineering, not astronomy. When people ask him for names of constellations in the sky, he draws a blank.

“Honestly,” he said, “I don’t know anything about stars.”